CANADIAN AIRMEN IN THE KOREA WAR:

PARTICIPATION AND TRAINING ASPECTS

Carl Mills (deceased 2019) was a Lieutenant Colonel in Canada's Air Force Reserve. Mills began researching the story of the Banshee jet fighter operations in the Royal Canadian Navy. After much research, travel, and many interviews, the book "Banshees in the Royal Canadian Navy" was self-published. Mr. Mills worked extensively on his next book, "The Canadian Airmen and Airwomen in the Korean War." This article is an excerpt.

By Carl Mills

Editing by Greg Neid, Malcolm Ramsay and Ken Murphy

Image Sources: RCAF History and Heritage, Harold Skaarup

PREFACE: From 1950 to 1953 Canada was part of the United Nations Forces fighting against North Korea. The belligerents in this war were North Korea backed by China and the Soviet Union versus South Korea backed by United States of America and The United Nations.

Japan's defeat in World War II brought an end to 35 years of Japanese colonial rule of the Korean Peninsula (Korea 1910, Manchuria 1931). The surrender of Japan to the Allied forces on 2 September 1945 led to the peninsula being divided into North and South Koreas, with the North occupied by troops from the Soviet Union, and the South, below the 38th parallel, occupied by troops from the United States.

The Soviet forces entered the Korean Peninsula on 10 August 1945, followed a few weeks later by the American forces who entered through Incheon. U.S. Army Lieutenant-General John R. Hodge formally accepted the surrender of Japanese forces south of the 38th Parallel on 9 September 1945 at the Government House in Seoul.

Although both rival factions tried initially to diplomatically reunite the divided nation, the Northern faction eventually tried to do so with military force. The North hoped that they would be able to unify the peninsula via insurgency, but the success of South Korea (Republic of Korea: ROK) in suppressing insurgency brought about the realization for the North that they would require military force. North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea: DPRK) had expanded their army and Korean volunteers fighting in Manchuria in the Chinese Civil War had given their troops battle experience. The North expected to win the war in a matter of days. Troops from North Korean People's Army (KPA) crossed the 38th parallel on 25 June 1950 beginning a civil war.

Canada in the Korean War - Wikipedia

INTRODUCTION

On 25 June 1950, North Korean armies overran the South Korean border and began a push towards the south end of the Korean Peninsula. The UN reacted and appointed the US President Truman as the executive agent to carry out the UN fight under a unified US Command. President Truman appointed General MacArthur, in addition to his duties in Japan, as the UN commander.

The push was ultimately halted, by South Korean and American troops, in a 100-square kilometre area in the southeast corner of South Korea, called the "Pusan Pocket". Vicious fighting broke out around the "Pocket" and the Americans and South Koreans lost even more ground.

In August, the "Pocket" was stabilized and plans for the daring Incheon Landing were underway. The Incheon Landing occurred on the west coast just below the 38th parallel, in September 1950, and was a surprising success. Forces from Incheon and the "Pusan Pocket" soon linked up and forced the North Koreans far into North Korea.

Canada committed 26,000+ military personnel, and served under either USA command or UN command until 1957 — after armistice until 1957 as peacekeepers.

By October of 1950, the UN had secured North Korean territory to within 100 kilometres of the Yalu River (the boarder between North Korea and China) and within 150 kilometres of Russia. During this time the UN enjoyed nearly complete air and naval superiority and the total capture of North Korea seemed complete. So much so that MacArthur declared that the war would be over by Christmas 1950.

However, in October, UN pilots were beginning to report a swept-wing jet fighter that would soon become known as the MiG-15. Even more significantly, the Chinese intervention had begun as they, unknown to the UN, amassed half a million troops just across the Yalu River in North Korea.

At this point, the Chinese took over the re-invasion of South Korea and began a massive and devastating surprise campaign against the UN forces. Many UN troops were trapped and several units were overrun as the Chinese pushed the UN to a point approximately 100 kilometres below the 38th parallel. Seoul fell for the second of four times during the war.

On April 11, 1951, President Harry Truman relieved General Douglas MacArthur of his command as head of UN forces in Korea for insubordination and public defiance of administration policies. MacArthur, who favored expanding the war into China, was replaced by General Matthew Ridgway to uphold civilian control over the military. President Truman feared that direct military involvement with China would lead to World War Three.

This offensive was halted by the end of January 1951, when the UN began its second counter offensive of the war. The Chinese were pushed to a point about 25 kilometres above the 38th in the east and 25 below in the west by mid-April, 1951. This area would change hands one more time with a final Chinese assault that was followed by a final UN offensive. By the end of June 1951 the see-saw activity stabilized and the demarcation line was roughly the same as that of the war-end line in July 1953.

Peace talks began when General MacArthur was relieved of his command by President Truman in April 1951. However, the war continued and the second portion, the remaining two years, was a war of skirmishes and attacks across the primarily stable demarcation line. Neither side seemed to be prepared to create an all out offensive to push the other significantly away from the prevailing demarcation area.

In March 1953, Stalin died and his successor, Georgi Malenkov, issued statements that opened the way for prisoner exchanges. Operation "Little Switch" was the exchange of wounded and ill POWs during April 1953. Peace talks were finalized on 27 July 1953 and the return of most remaining POWs, during operation "Big Switch”, took place in August 1953.

INITIAL REACTION BY CANADA

At the outbreak of the Korean War, Canada was heavily committed to supporting the build-up of air power in Europe and the protection of sea-lanes in the North Atlantic - both under NATO. Decisions had to be made about splitting these commitments and thus allowing significant participation in Korea or staying primarily with the NATO commitment.

As an initial reaction, the Canadian military immediately committed the non-NATO transport capabilities of the RCAF's 426 Transport Squadron (from their base in Dorval) and dispatched three RCN destroyers (from their base in Esquimalt BC).

The enterprising CEO of Canadian Pacific Airlines, Grant McConachie, whose aircraft were already, with the permission of MacArthur, flying into Tokyo, suggested that he could provide a charter service for the US Army. The US Army accepted this concept and the Canadian government financially backed this commitment as part of Canada's contribution to the Korean airlift. By the end of the war, CPA had provided over 700 military charter flights from Vancouver to Tokyo.

Three senior military observers, one from each service, were sent to report on the seriousness of the war and to make recommendations regarding Canada's further participation. All three observers were in Korea in the very early stages of the war. All three began their tours in the "Pusan Pocket". Although the details of the Army and Air Force activities are not yet researched, it is known that Lieutenant Colonel Frank White and Wing Commander Harry Malkin followed the advancing war to Seoul and then returned to Canada, and that the Naval observer's activities were most energetic.

Lieutenant Commander Pat Ryan, a naval aviator, was sent to observe ground and naval forces and make a recommendation to the RCN. Ryan arrived in Korea in time to participate in the dangerous Pusan break out. He was actively employed by the USAF as a jeep radio operator where he ground-controlled friendly aircraft against enemy installations. He accompanied the US Army's 5th Cavalry from the Pusan Pocket up to Pyongyang, the North Korean capital. Here he left the 5th and then joined the USN's Task Force 77 in the Sea of Japan to continue his observations.

MiG Alley, along the Yalu River was where USA and Canadian made F-86's and Mig-15's participated in "dog fights".

In Task Force 77, aboard the USN's aircraft carrier the USS Philippine Sea, Ryan flew several combat missions aboard AD-4Q Skyraider aircraft. He acted as an anti-ECM operator against targets that were defended with radar controlled anti-aircraft artillery. From here he served on the UK's aircraft carrier, HMS Theseus, an Australian ship, and then returned to Canada.

A few other Canadians were involved in the Korean conflict at that time. The RCAF's Flight Lieutenant Omer Levesque was on bona fide exchange duties with an F-86 equipped USAF squadron in the US. This squadron was called into Korean duty and Levesque accompanied the unit to Korea.

While there he accomplished one MiG-15 kill in the famed "MiG Alley" area, however, his unit was evacuated from  Kimpo (near Seoul) when the Chinese overran the area in December 1950.

Kimpo (near Seoul) when the Chinese overran the area in December 1950.

After flying in the defence of Northern Japan, he returned to Korea for more air duty. In June, his tour ended and he returned to Canada with the award of the US Air Medal and the US DFC. Coupled with his four previous "kills" during the Second World War, he became Canada's last fighter pilot "ace". On his return to Canada, he was assigned to the F-86 OTU at RCAF Stn Chatham as the Chief Flying Instructor.

Canadians, George Hanrahan and Richard Proctor, joined the US Marines and the USAF, respectively, as radio operators. Both were assigned to Korea in the early months of the war and both spent a turbulent year in Korea with combat ground forces. Hanrahan was wounded in action and both eventually repatriated to Canada.

Canadian Aircraft

Logistics

435 Squadron Dakota Transport

435 Squadron C-119 Fairchild Flying Boxcar

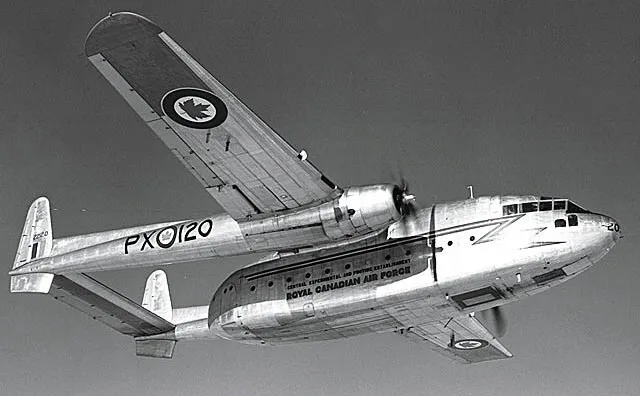

426 Squadron Canadair North Star

412 Squadron de havilland Comet

Combat

Auster Artillery Spotting

T-6 Texan Reconnaissance "Mosquito"

Canadian Air Casualties

Captain Joe Liston, AOP pilot, shot down by flak, taken Prisoner of War 1953-August-15

Squadron Leader Andrew Mackenzie DFC, shot down, taken prisoner of War 1952-December-05

FURTHER CANADIAN INVOLVEMENT

Worldwide and Canadian thinking about Korea at the outbreak of the war was that it was merely a “police action" and that the real communist threat still remained in Europe. For this reason, the RCAF's fighter capability and build-up remained focused on Europe.

Similarly, the Communist never indicated any form of submarine warfare - in fact the North Korean naval participation was almost non-existent throughout the conflict. The main thrust of UN naval power was the support of interdiction activities, bombardment during significant landing, mine laying or clearing, and coastal patrols. For this reason, the Canadian government reaffirmed the retention of its ASW fleet in the North Atlantic. However, with the surprise Chinese intervention in October of 1950, the UN member nations, including Canada, began to realize the magnitude of the impact of the combined Chinese and North Korean forces coupled with support of the Russians. They realized that more UN support was required.

Canadian Casualties

| Combat-related deaths | 312 |

| Non-combat (accidents/illness) | 204 |

| Total Deaths | 516 |

| Wounded | ≈1,230 |

| PoW's | 32 |

| Missing in Action | 16 |

ARMY

As the Korean crisis deepened, the Canadian Army quickly organized the Special Forces concept to meet Korean and other NATO commitments. The Special Forces recruits were committed to 18 months military service and, for Korea, this meant about six months of training and one year in Korea. The Special Forces were attached to existing regiments such as; the Royal Canadian Regiment, the Lord Strathcona's Horse (RC), the 81st Field Regiment, the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery, the Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI), Royal 22nd Regiment and the Queen's Own Rifles of Canada. These units were rotated through Korea and also on and off front line duties. Several other significant units provided support in the areas of engineering, medical, dental, provost, pay, chaplaincy and intelligence.

The first unit selected for Korean duty was the 2nd Battalion of the Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI). They entered combat in February of 1951 and particularly distinguished themselves in the Chinese second offensive at Kapyong. The Canadians fought alongside regiments from New Zealand, Australia, and the UK.

Other Units of the Canadian Brigade, consisting of several regiments, arrived in Korea in May 1951 and were soon involved in the fighting. The overall tactics in Korea were not to close with the enemy but rather to force the enemy back. The objective was to regain the 38th parallel. The final line, the "Jamestown Line" was achieved after several battles involving the regiments of the Canadian Brigade - including infantry, artillery and tank corps.

The Canadians were assigned a 7,000-metre length of the "Jamestown Line" alongside American and other commonwealth troops. The positions were supported by UN artillery including the Canadian Regiments. In July 1951, truce talks began but difficult fighting still prevailed. Although the "Jamestown Line" remained relatively stable until the end of the conflict, there were many vicious fights including instances where positions were overrun by swarms of Chinese invaders and the Canadian defenders had to call in friendly artillery support on top of their own positions.

The Army contribution to Korea elevated Canada's contribution to the third highest of participating United Nations members: third to the Americans and British. Of the nearly 27,000 Canadian military participants in Korea. 22,000 were from the Army. Of the 33 PoWs, 32 were from the Army and of the 516 Canadian war dead, 506 were from the Army. There are still 16 Army MIAs from Korea.

NAVY

In addition to observer, Lieutenant Commander Ryan. the RCN sent one other naval aviator, who flew combat missions with the USN, and five additional destroyers. All eight destroyers were assigned to the British Command on the west coast blockade, but also took their turns serving in east coast operations. The ships supported the  lnchon Landing, were involved in escort and patrol duties, bombardment of enemy positions and the support of the major evacuations during the Chinese intervention. There were nine RCN naval fatalities during the Korean War.

lnchon Landing, were involved in escort and patrol duties, bombardment of enemy positions and the support of the major evacuations during the Chinese intervention. There were nine RCN naval fatalities during the Korean War.

AIR FORCE

The Canadair built Sabres were designated F-86-E. They were Mk 2 to the RCAF. The engine was General Electric J47-GE-13, 5200 lbs thrust. Orenda 10 engines were not introduced until Mk 4, 6500 lbs thrust. (One Mk 3 had Orenda 3, 6000 lbf). The Orenda engines did not see service in Korea.

The USAF and RCAF wore G-suits, the Chinese did not; just WWll type flying gear. So USAF and RCAF pilots were able to withstand higher G-forces. So even though the F-86 was inferior in turning, it turned tighter than the MiG-15 because the better equipped and trained pilots could withstand the higher G-forces in tight turns and evasive maneuvers.

The MiG-15 was lighter, flew higher, and was more maneuverable, initially. The Chinese preferred to do combat at high altitude, and swoop down on the Sabre, then climb. Armament was 23mm cannons, with greater range and fire-power. However, at high Mach numbers, in the transsonic range, the aircraft became "snaky", which meant the cannons were not as accurate.

The last 40 of the 60 Canadair USAF F-86Es had leading edge slats that functioned automatically at low speed and high G-force, to make the aircraft more maneuverable. In conjunction with the improved wing, this Sabre introduced the all-flying tail-plane, which felt like power steering, and provided longitudinal stability, making gunnery more accurate.

The kill ratio of Sabre versus MiG-15 is disputed, but modern analysis places it at between 1.8 to 5.6 to one in favour of the F-86 Sabre. The favourable ratio is due to more experienced better equipped pilots, not a better aircraft.

Four US Air Force North American F-86E Sabre fighters of the 51st Fighter Interceptor Wing over Korea on 22 May 1953. The aircraft FU-649 (s/n 50-649) and FU-653 (50-653) are F-86E-5-NA models, FU-793 (51-2793) is a F-86E-10-NA, whereas FU-882 (52-2882) is a F-86E-6-CAN that was originally built by Canadair (ex-RCAF 19351), but delivered to the USAF. 50-653 is today on display at Hickam Air Force Base (Honululu International Airport), Oahu, Hawaii. source: Harold Skaarp https://silverhawkauthor.com/aviation/north-american-f-86-sabres-flown-by-canadians-on-exchange-with-the-usaf/

In addition to the full activities of 426 Transport Squadron, the RCAF increased its contribution by developing a volunteer system for F-86 pilots, the loan of Nursing Sisters to the USAF, the involvement of 435 Squadron, and the use of several RCAF technical officers and men and other specialist participants. Thirteen nurses were all commissioned RCAF officers who were seconded to the USAF MATS system. These nurses were employed onboard USAF C-54 aircraft over the South Pacific to assist in the return of wounded soldiers. Each spent about four months on this duty as well as accompanying some similar RCAF North Star flights.

435 Squadron flew the C-47 Dakota and the C-119 Flying Boxcar and were employed to bring Canadian wounded from  McChord AFB in Washington State to Vancouver and Edmonton. Not much is known about the technical staff, however, other specialist were also sent to Korea by the RCAF. Wing Commander Edward C.R. Likeness was in Korea for three weeks in November 1951. He was sent to observe intelligence and photo interpretation capabilities at Kimpo prior to taking command of a similar unit in NATO. Squadron Leader J.T. Reed served with a USAF MATS Unit in Japan. He was awarded the US Bronze Star for outstanding duty. Group Captain Keneth R. Patrick was sent to Korea by the US and Canadian governments to analyze communist radar and counter-measure capabilities, in December 1951. He flew on five operational missions in USAF B-29 aircraft over North Korea. We have just located Group Captain Patrick's detailed "top secret"(at the time) report on these missions.

McChord AFB in Washington State to Vancouver and Edmonton. Not much is known about the technical staff, however, other specialist were also sent to Korea by the RCAF. Wing Commander Edward C.R. Likeness was in Korea for three weeks in November 1951. He was sent to observe intelligence and photo interpretation capabilities at Kimpo prior to taking command of a similar unit in NATO. Squadron Leader J.T. Reed served with a USAF MATS Unit in Japan. He was awarded the US Bronze Star for outstanding duty. Group Captain Keneth R. Patrick was sent to Korea by the US and Canadian governments to analyze communist radar and counter-measure capabilities, in December 1951. He flew on five operational missions in USAF B-29 aircraft over North Korea. We have just located Group Captain Patrick's detailed "top secret"(at the time) report on these missions.

On two of his missions, two of five and three of five accompanying B-29s, respectively, were shot down. Although Group Captain Patrick was a Second World War Group Captain, he reverted back to Flight Lieutenant at war's end and joined the RCAF Reserves. Eventually, he regained the rank of Group Captain and was the only RCAF reservist to serve in Korea.

Squadron Leader Alan J. Simpson spent two months in Korea, October and November 1951. He was there to observe and participate in photo and intelligence operations at Kimpo with the 67th Tactical Reconnaissance Wing. Before being instructed not to fly on combat missions, he participated in one operational flight that lasted five hours. The flight crossed Korea and proceeded up the enemy east coast. The USAF RB-26C aircraft encountered flak twice during the flight but was not hit.

De Havilland Canada sent a sole technical representative to Korea in order to service the Canadian-built DHC-2 Beaver aircraft (designated the L-20 by the US Army). Bruce Best, a civilian aero maintenance engineer, spent one year (mid-1952 to mid-1953). His technical background was excellent and he accomplished seventeen significant field modifications in Korea that enabled the aircraft to over come environmental difficulties and hard use by front-line US Army pilots. The hundreds of Beavers became known, along the Korean front lines, as the "air-jeep". Although he was checked out on the Beaver in Canada, he was not allowed to fly solo by the US Army in Korea. Although there is good indication that RCAF technical staff were employed with the USAF at major F-86 bases such as Suwon, there is no information, as yet, about their activities.

CANADIAN AIRMEN PARTICIPATION AND IMPLICATIONS OF TRAINING

Army AOP Operations

In August 1952. the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery, began sending a string of four Air Observation Post Pilots (AOP) to Korea. They flew Auster aircraft with the 1903 Independent Air Observation Post Flight a part of 656 Squadron RAF. They were part of the Commonwealth Divisional HQ, and suported artillery and infantry action along a portion of the "Jamestown Line”.

The four Canadian AOP pilots were all accomplished artillery officers. All had served in these roles either during the Second World War or had training and several hundred flying hours in the Auster aircraft in Canada prior to going to Korea.

Captain Joe Liston, the first Canadian AOP pilot, was shot down and captured during his twelfth combat mission. He was hit by radar-controlled flak at seven thousand feet and parachuted into enemy territory. He was twice rendered unconscious in the air and shot at before alighting into a group of Chinese soldiers and taken as a PoW.

Captain Peter Tees replaced Liston in September 1952. Tees was an energetic participant in Korea and accomplished 211 combat missions. He served in the harsh cold climate of Korea that tested both the pilots and the machines in the often two-hour long flights. He had three engine failures - one resulted in the total destruction of the machine. He also survived the spectacular hit of friendly artillery round at 7000 feet. Although the wing was quite shattered it remained intact enabling him to return to base. The round came from a piece that he was controlling and, in addition to the obvious embarrassment and the drinks that he would have had to provide to his comrade tormentors, it must have brought profound comment from him at the time.

Captain Tees was a successful combatant and often directed Canadian artillery units that were supporting Canadian infantry in skirmishes with the enemy along the active front lines. For his outstanding duty, he was one of two Canadians in Korea to be awarded the Commonwealth DFC, the only Canadian Army pilot to do so since the First World War and the last known Canadian to be awarded this, substantially, Air Force medal.

The third pilot, Lieutenant Keith Johnstone, managed 17 combat missions before the cease-fire in July 1953. He, along with the fourth pilot, Captain Gerry McDonald, endured a tour with very little combat excitement.

Captain Liston was released from prison during operation "Big Switch" in August 1953. His return was all but ignored by the Canadian Army so it is not likely that his POW experience had any impact. Captain Tees became the CO of the AOP flight at Camp Petawawa, however, the results of his experiences in Korea, substantially, had very little impact on the AOP flight operations in Canada. The methods and equipment used in Canada were the same as in Korea and very little change was needed. All four remained with the Army until their retirement.

"Mosquito" Operations [AT6 Texan or Harvard equivalent]

During the tenure of the Canadian Regiments, a USAF air operation called "Mosquito" had evolved and was operating along the front lines (The term "mosquito" evolved from the well known buzz of that aircraft).

Missions were flown exclusively by members of a USAF unit called the 6147 Tactical Control Group. The 6147th consisted of two flying squadrons - the 6148th and 6149th. These two squadrons were, in turn, supported by USAF-staffed, infantry-positioned, ground parties, the 6150th Tactical Air Control Parties (TACP), and an overall command and airborne control centre. The "Mosquitos" were extremely effective and saved countless UN ground forces lives.

The primary duty of the "Mosquitos" was to control all tactical air strikes between the front lines and the bomb line so as to inflict the maximum damage to the enemy while ensuring the highest possible degree of safety to the friendly forces. This was done by preventing the friendly fighters and bombers from accidentally attacking the friendly troops by adequately marking targets with smoke rockets.

The "Mosquitos" had other roles such as seeking out targets, directing air attacks, investigating suspected targets that were found in aerial photos or reported by other aircraft or ground forces. The aircraft carried twelve rockets, however, frequently the "Mosquitos" were forced to fly above suspected targets and drop smoke grenades over the side of the aircraft in order to adequately mark them.

This activity was conducted from unarmed T-6 aircraft (called Harvards in Canada). The pilots were primarily USAF while the back seat observers/air directors were from a variety of United Nations backgrounds. Canada provided, on a three to four-month secondment basis, sixteen "back seaters". All were officers and were from the infantry, armoured or artillery regiments. This type of flying was the most dangerous of all flying in Korea. The enemy knew full well that if discovered by the "Mosquito" an air attack would soon unfold upon them.

Air attacks included lethal and concentrated doses of napalm, 500-pound bombs, rockets, machine gun and 20 mm cannon fire. These munitions were expertly delivered by Air Force, Marine, and Navy pilots who were orbiting nearby waiting for instructions from the "Mosquitos". There was a definite incentive to shoot the "Mosquito" and many were. Fortunately, only two Canadians were wounded (Lieutenant AP Bull and Captain JRPP Yelle) and only one was shot down (Lieutenant AG MaGee) but survived during this type of activity. Unfortunately, one Canadian "Mosquito" was killed during a post-war training accident in Korea, Lieutenant Neil Anderson QOR of C, is buried at the UN cemetery in Pusan, Korea.

Short training programs for successful "Mosquito" back-seat candidates and familiarization flights were provided at the USAF Flying Units the 6148th and the 6149th TACS. The ability to achieve air-to-ground information and successfully spot and mark targets, direct the delivery of incoming, high-speed explosives dropped from above from orbiting, high-speed combat aircraft, while in an either a too-hot or too-cold, noisy, bouncing, unarmed, slow-flying aircraft with poor in-cockpit radios, that was often flown by an aggressive young pilot with a heavy southern drawl, and while being shot at, came with on-the-job-training.

The activities of the "Mosquito" units were not a part of Canadian military doctrine. Therefore, there was no training of the sixteen volunteers prior to Korea nor was there any impact on Canadian Army training after Korea.

Navy - Jet Fighter Pilot

Other than Lieutenant Commander Ryan and other naval aviators who were serving sea duty on RCN ships in Korea, there was only one Canadian naval aviator who was directly involved in combat flying duties in Korea, In addition to his advanced flying status with the RCN, Lieutenant J.J. MacBrien, in 1951, was sent on a special air weapons course with the Royal Navy in the UK. This was an intensive course involving classroom and flying skills to develop and accomplish air tactics. The finale to the program was 25 hours of jet fighter time. On his return to Canada, he volunteered for duty with the USN. He was assigned to VF-781 where he trained on the F9F-2 Panther jet. His squadron was soon selected for Korean duties. Because of the course with the RN, he was appointed the squadron air weapons officer. He instructed the squadron on the weapons, air-to-air and air-to-ground tactics.

The squadron prepared for several months including all forms of aircraft handling, weapons, survival, and finally conversion to the F9F-5 - a more powerful version of the Panther. The squadron would fly and fight with other units aboard the USS Oriskany, one of up to four carriers in Task Force 77, which was on station in the Sea of Japan.

During his tour in Korea, he flew a variety of missions including; combat air patrols, fighter-bomber missions, photo escort, flak suppression, close support, and armed reconnaissance. He learned invaluable lessons regarding flights over enemy territory, carrier operations, poor weather operations, training of wingmen, and gained experience at leading formations into combat. He accumulated 233 hours and 92 carrier landings in jet fighters and completed 66 combat missions. He was awarded the US DFC for a particularly successful and difficult mission.

On his return to Canada, he was posted to non-flying sea duty, which was a requirement for all naval aviators. However, in spite of the fact that he was the only RCN pilot with jet combat experience and, in spite of the fact that the RCN was about to purchase the McDonnell Banshee jet fighter (1953 -1955) to replace the aging Sea Furies, he was assigned to a headquarters position after his sea duty. He was subsequently promoted to Lieutenant Commander but soon resigned from the RCN and never flew again.

Air Force - 426 Transport Squadron

426 Transport Squadron began receiving the North Star aircraft in September 1947. 1n the three years from then, and prior to the commencement of "Operation Hawk", the squadron developed an outstanding capability to operate as a squadron and to operate the aircraft. The squadron was well established, had superior leadership and all support and training systems were in place.

426 Squadron was located at RCAF Station Lachine, in Quebec, where acceptance checks and limited training was initiated in 1947. In March 1948, long-range training began with a flight to Edmonton. With ten aircraft on strength, flights were soon regularly operating to both coasts. in May 1949, the first trans-Atlantic flight took place. The aircraft were regularly flying the Prime Minister to western Canada, and also participated in the 1949 Canadian National Exhibition air show in Toronto. The squadron, by early 1950, was serving military requirements in the Arctic and flew the first non-stop coast-to-coast flight. Aircrews were a mix of Second World War veterans, newly trained pilots and other aircrew. Conversion and training to the North Star took place at the squadron level under the direction of experienced and well-trained aircrews.

Just two weeks after the North Koreans invaded, 426 was alerted to move to the USAF's McChord AFB at Tacoma, Washington to participate in "Operation Hawk" the Canadian military portion of the Korean airlift. The instructions to 426 Squadron were specific; they would have twelve "war-strength" aircraft, would integrate with the USAF MATS service, cease all domestic flights except those that were essential and would operate into Japan but not Korea.

The squadron, with six aircraft and 275 personnel departed Dorval on 25 July. On their departure, the six aircraft flew to Ottawa to pay an airborne tribute to Prime Minister MacKenzie King who was lying in state at the Parliament Buildings. Remarkably, three loaded aircraft departed Tacoma on the first operational flights destined for Tokyo on the 27th of July. This was the beginning of a new area for the squadron; one of intensity and challenge as the Pacific routes had never been flown before by the RCAF. The flights over the North Pacific called for careful planning to deal with the severe and unpredictable weather and the flights over the South Pacific required precision to deal with the long legs over open water.

The weather in the Aleutian Islands is as bad as any weather that can be found anywhere in the world. The mountainous chain of islands is like a spine stretching into the southwest Pacific Ocean for about 1,100 miles from the west coast of the Alaskan Peninsula. The Pacific Ocean, with the relatively warm Japan current moving through from west to east, is on the south side and the very cold Bering Sea is on the north side. The constant mixture of cold water and cold air from the north with the warm water and warm air on the south side causes this worst weather situation for most of the year.

Shemya [Airforce Base], the crucial stop-over point for all flights to and from Japan, is at the extreme tip of the Aleutian Islands and at the mid-point between Tokyo and Anchorage, Alaska. To combat the weather conditions, the USAF provide one of their best GCA services and top-caliber controllers to ensure safe arrivals at the airfield. In spite of this and in spite of the six-hundred foot wide runway, accidents happened. One RCAF North Star, after making a safe landing in a blinding snowstorm and in a heavy crosswind, was blown off the slippery runway. Although there were no injuries and no cargo lost, the aircraft was destroyed.

Shemya [Airforce Base], the crucial stop-over point for all flights to and from Japan, is at the extreme tip of the Aleutian Islands and at the mid-point between Tokyo and Anchorage, Alaska. To combat the weather conditions, the USAF provide one of their best GCA services and top-caliber controllers to ensure safe arrivals at the airfield. In spite of this and in spite of the six-hundred foot wide runway, accidents happened. One RCAF North Star, after making a safe landing in a blinding snowstorm and in a heavy crosswind, was blown off the slippery runway. Although there were no injuries and no cargo lost, the aircraft was destroyed.

Other reports indicate that weather predictions were also unreliable at Shemya. One aircraft took-off in a snowstorm, expecting clear weather at ten thousand feet. At fourteen thousand feet, after losing radio contact and having accumulated a maximum amount of ice, had to carry high engine power for the entire flight to Japan. Flying as low as fifty feet over the ocean and below a solid cloud cover, they made an emergency landing at Misawa in northern Japan.

When they pumped the fuel from all tanks into one, the fuel level was so low that they were unable to measure the remaining fuel quantity. In spite of these winter hazards, the northern route was ten hours shorter than the southern route, via Hawaii and Wake Island, and was the preferred route during the summer. The standard full-tank endurance of the North Star was 14 hours 30 minutes. The leg from Honolulu to Travis AFB, near San Francisco, was slightly beyond the safe range limits for the North Star with some flights taking between 12 and 14 hours. It was particularly tricky, eastbound, if weather extended well in-land from San Francisco. One flight, on a westbound leg into Honolulu's Hickman field, ran out of fuel on the runway after landing.

Each navigation leg had its tests particularly the Shemya to  Haneda (Tokyo) leg - radio aids existed at each end of the run but were only good for the last several 100 miles or so. Land to the west was hostile Russia and radio jamming was a way of life along this leg. The Pacific routes offered excellent training for navigators. In addition, navigators and radio operators often acted as co-pilots over the long legs and the pilots often took the sextant in hand to assist in the navigation.

Haneda (Tokyo) leg - radio aids existed at each end of the run but were only good for the last several 100 miles or so. Land to the west was hostile Russia and radio jamming was a way of life along this leg. The Pacific routes offered excellent training for navigators. In addition, navigators and radio operators often acted as co-pilots over the long legs and the pilots often took the sextant in hand to assist in the navigation.

The experience achieved from the few years of operations proved invaluable. Although there were several close calls and incidents, there was only one squadron fatality (Flight Sergeant Herbert Thomas MacDonnell Sept. 1953), no passenger fatalities, and no cargo lost. Operation Hawk provided excellent training for the squadron; integration with the USAF, long range navigation, continuous operation and maintenance from remote airfields, deployment of personnel over long periods of time, constant use of real GCA, and experience in handling a variety of cargo types from wounded soldiers to munitions. 426 Squadron enjoyed an excellent rapport and reputation with the USAF. The Squadron also employed some USAF pilots on bona fide exchange duties.

During "Operation Hawk", 426 Squadron flew 599 round trip missions between McChord and Tokyo and several unauthorized flights into Korea, all between July 1950 and June 1954.

Jet Fighter Pilots

Jet fighter training in the RCAF commenced in 1948 when the Vampire jet fighter was issued to 410 Squadron at RCAF Station Saint-Hubert. An OTU was formed there but it soon moved to RCAF Station Chatham in New Brunswick. Note that NATO was also formed in 1948, which committed Canada to a significant air defence role in Europe. Canada's commitment was to initially provide 12 squadrons of F-86 aircraft for the four wings, which were to be based in Europe. This commitment began unfolding with the production of F-86 aircraft at Canadair. The first F-86 flew there in August of 1950, about one month after the Korean War broke out and about the same time that the MiG-15 was first seen in Korean skies.

The Korean years were a hectic time for the RCAF. The twelve fighter squadrons were formed, eventually equipped with the F-86, shaped into fighter wings, and located into Europe - all in the almost exact time frame as the Korean War. In addition, the CF-100 program was underway with the first squadron equipped during the final phase of the Korean War. Also during this time, the RCAF equipped with the Comet Airliner and the C-119 Flying Boxcar aircraft.

Clearly, there were no resources available to make any significant fighter commitment to the Korean War. By June 1951, Flight Lieutenant Omer Levesque had completed his tour as a bona fide exchange pilot with the USAF in Korea. He had good success in Korea accomplishing one MiG-15 "kill" and gaining valuable experience - exactly the experience required for the new squadrons heading for Europe. Because of this impact, the RCAF considered that Korea would be a good training ground for new F-86 pilots. A schedule, allowing approximately two "qualified" pilots per month, was set up and "volunteers" were invited to apply. It was initially thought that the younger, less experienced pilots would best benefit from the experience in Korea. The requirements for duty in Korea were simple a minimum of 50 flying hours in the F-86.

The individual commitment was 50 combat missions or a six-month tour; which ever came first. All flying would be done with the USAF 5th Air Force at either the 4th FW at Kimpo or the 51st FIW at Suwon. However, there was about a one-year hiatus. after Levesque, before the other twenty-one RCAF F-86 "volunteers" began arriving for duty in early 1952.

The first Canadian built F-86s were delivered to 410 Squadron in March 1951 and two more squadrons were equipped in the same year. The heart of the F-86 training program was eventually the OTU at Chatham, however; so important was the European commitment that the first F-86 did not arrive at the OTU until February 1952 - about the same time as the "volunteer" program began for Korea. The OTU did not have a great impact on the F-86 qualifications of the pilots going to Korea. All pilots who went to Korea had received their initial jet time on the Vampire, by-and-large, through conversion programs at the various squadrons. Several pilots who were accepted for a tour in Korea had to scramble to achieve the minimum 50 hour requirement. Often this time was spent "boring holes in the sky" to accumulate the time. Some Canadian pilots arrived in Korea and required training, having never fired the F-86's guns.

The training experience of the twenty-two pilots involved in Korea fall into four categories;

- WW2 pilots with significant jet experience

- WW2 pilots with minimal jet time

- Post-WW2 pilots with significant jet experience

- Post-WW2 pilots with jet time.

The fifth pilot, sent to Korea in early 1952, fell into the later category. It is rumoured that he was sent as a form of punishment for a flying incident. Upon his arrival at the 4th F1W at Kimpo, the USAF Wing Commander gave him the customary interview. The Commander decided that the twenty-year old "pipeline" pilot was too inexperienced and would be a danger to himself and others that would rely on him in combat. He was sent back to Canacia without any flight time in Korea. This was an embarrassment to the pilot and to the RCAF. The incident did have an impact on the RCAF's future choices as all future candidates were either Second World War experienced, instructors at the OTU, or had significant F-86 time. In the end, 17 of the 22 F-86 pilots were Second-World-War experienced.

Training varied in Korea but, by-and-large, was an on-the-job experience. Most went through an initial, on-squadron, mini program called "clobber college". This was a short flying program that dealt with the realities of combat flying in Korea. The very experienced and capable entered combat after a few local familiarization flights. Usually these pilots after a few missions were given some status such as an element leader (two aircraft) or section leader (four aircraft). Others, with experience, were destined to fly as wingmen for the various squadron commanders. If a pilot achieved strikes on a MiG, "damaged", "probables", or "kills", they were given these positions almost automatically.

Of the 22 pilots sent to Korea, substantially, only 16 flew their full combat tour. Of these, nine accounted for all of the 21 MiG encounters including nine "kills", two "probables", and ten "damaged". Of these nine, three pilots accounted for 14 of these encounters. Sixteen of the encounters took place in the six months between early 1952 to late 1952. Substantially, the Second World War veterans had better success accounting for 19 of the MiG encounters. Canadians would have had more opportunities if their tours had been the same as the USAF at 100 vs. 50 combat missions.

The types of combat missions in Korea were; sweeps and patrols deep into enemy territory (MiG Alley), fighter-bomber and photo recon escort, stand-by, scrambles and airborne alert, weather recon over intended battle areas, search or CAP for downed pilots. Other non-combat flying included maintenance ferry flights to Japan and orientation training of newly arrived pilots. Those who completed their required 50 combat missions usually had about 70 hours of combat flying and 20 hours of non-combat. All who finished their combat tour did so within three to four months.

The experienced gained in Korea included; tension of actual combat, flight leadership and decision making in the air, dealing with battle damage, experience while being shot at or shooting at someone, importance of flight doctrine and wingman duties. Most pilots encountered some sort of in-flight incidents from being shot down to engine failure and ejection, and flameouts far from base accompanied by dead-stick landings. Most of the pilots were shot at; encountered flak, or small arms fire during the varied missions. The MiG-15 was capable of flying higher and faster than the F-86. It is considered that "MiG Alley" was used as a training area for the communists, Certainly the UN pilots cold tell when the better trained were flying instead of the new pilots. Their tactics usually included a climb from their sanctuary north of the Yalu River until they were safely above the maximum F-86 altitude, fly south over top of the Sabres, and then turn and dive for home shooting at the F-86 as they flew through the formations. To counter this, the Sabre pilots would stack up in groups at various altitudes and catch the MiGs as they went past. With the two aircraft looking alike it was a tricky business and F-86s were shot down by F-86s on more than one occasion. When the MiGs were reluctant to come down and fight the UN pilots often set themselves up as decoys, purposely contrailing or otherwise trying to draw the MiGs into a fight. They consistently took on superior numbers of MiGs.

In 1952, Canada provided 60 F-86 "Sabre 2" aircraft to the USAF for operations in Korea. They were designated the F-86-E-6 and had somewhat better performance than the US F-86-E. Approximately 20% of all combat missions flown by Canadians were in Canadian-built Sabres. Necessarily, some MiG events were also encountered by Canadians in these aircraft including the three "kills" and two of three "damaged" by Flight Lieutenant Ernie Glover, Flight Lieutenant Claude LaFrance's MiG "kill", the Flight Lieutenant Bob Carew ejection, and two of Squadron Leader Doug Lindsay's “damaged" - eight confirmed encounters of the 21 known.

The second highest Canadian MiG score was obtained by Squadron Leader Doug Lindsay with two "kills" and three "damaged". The highest score was obtained by Flight Lieutenant Ernie Glover with three "kills" and three "damaged". For his exploits in Korea, Glover was awarded the Commonwealth DFC. He was the second last Canadian and the last Air Force pilot to receive this award. The training in Korea after the peace accord was different. Because Canadians could not achieve combat missions, three pilots were obliged, under personal protests, to complete the "six month" requirement of their commitment. Although the squadrons flew armed photo recon escort duties, while being shadowed by MiGs, up both coasts on a daily basis, there were more formal air exercises and gunnery practice. Other opportunities also prevailed and one pilot checked out on the C-47.

The single most significant event for the RCAF in Korea was the shooting down of Squadron Leader Andrew MacKenzie in December of 1952. On his fifth combat flight, he was inadvertently shot down by a USAF Sabre and spent two years as a convicted United Nations spy in Communist China. This sentence took him one year beyond the end of the war and he spent 16 months of the term in solitary confinement. Similar to POW Captain Liston, neither family knew that they were alive until they were near release. Both of their wives were expecting when they were shot down.

The most infamous quote came from Flight Lieutenant Bob Lowry, who was on a combat mission, when he radioed that he could use some assistance as he had several MiGs cornered at his six o'clock. By-and-large, the Canadian fighter pilots were considered excellent combatants - they were known for their aggressive nature in air combat and were dedicated to their role in Korea. By December of 1953, all RCAF fighter pilots had departed from Korea. With the exception of one, all Canadian Korean War pilots returned to F-86 duties either in Canada or Europe with the Air Division. At least three became involved in CFI duties at the Sabre OTU at RCAF Stn. Chatham while others were instructors. Several USAF Korean War veterans, on exchange duties with the RCAF, also instructed at the Sabre OTU after Korea.

COMBAT MISSIONS

- The RCAF accounted for 894 combat missions over North Korea.

- The Army AOP pilots accumulated 241 combat missions.

- The "Mosquito" observers accounted for an estimated 800 missions.

- The RCN accounted for 66 combat missions.

- The estimated total Canadian combat missions in Korea is 2,000.

- The estimated total UN combat missions in Korea is 750,000.

Note that combat missions do not include the activities of 426 Squadron or flights in combat aircraft that were not assigned to combat missions.

AWARDS, MEDALS, AND COMMENDATIONS

If awards and medals are any indication of training and achievement, then the Canadian airmen did very well. They received no less than 57 Commonwealth and US awards, medals and commendations. This number would have been higher except for a Canadian rule at the time. Canadians were only allowed to receive one US award. Primarily this meant, in several cases, accepting the US DFC but not the US Air Medal. The US Air Medal was generally given for 30 combat missions while the US DFC was given for 75 combat missions or for participation in some significant air event - this would include a MiG "kill".

CLOSING

One sunny, spring, Sunday morning a few months ago. I was enjoying a coffee and listening to a radio commentary regarding the war in Viet Nam. The guest speaker was explaining certain details and used a comparison with the Korean War. One remarkable statement was - "in 50 years, most people will not know much about Viet Nam or Korea and of those who do, many will not know which came first.” Our research, presentation, and publication are vital to the preservation of our country's military heritage.

APPENDIX

LIST OF KNOWN PARTICIPANTS

CANADIAN ARMY - AOP

- Captain JM Liston (RCHA) (POW)

- Captain PJA Tees (D) (RCHA) (COMM DFC)

- Lieutenant K Johnstone (D) (RCHA)

- Captain G McDonald (RCHA)

MOSQUITO [Texan T-6]

- Lieutenant NM Anderson (D) (QOR of C)

- Lieutenant AP BuIl (D) (PPCLI) (US AM)

- Captain RB Cherrett (D) 2RCR)

- Captain LR Drapeau (D) (R22eR) (US AM)

- Technical Sergeant GT Hanrahan (with USAF)

- Captain H Hihn (D) (2RCR)

- Captain JH Howard (D) (RCHA) (US AM)

- Captain JJHR Lamontagne (D) R22eR)

- Lieutenant KD Lavender (81 Fd Regt RCA)

- Lieutenant DG MacLeod (2PPCLI) (US AM)

- Lieutenant AG MaGee (1RCR) (US DFC)

- Captain JF0 Plouffe (R22eR) (US DFC)

- Technical Sergeant RT Proctor (with USAF)

- Technical Sergeant WT Ramsay (with USAF)

- Captain CJ Rogers (D) (2RCR)

- Lieutenant WC Robertson (1PPCLI) (US AM)

- Captain JPR Trembly (D) (R22eR) (MC*)

- Lieutenant WE Ward (LdSH(RC)) (US DFC)

- Lieutenant PJV Worthington (3PPCLI)

- Captain JRPP Yelle (R22eR) (US DEC)

Captain Trembly partially awarded MC during single "mosquito" flight

ROYAL CANADIAN NAVY - OBSERVER

- Lieutenant Commander (P) P Ryan

FIGHTER PILOT

- Lieutenant (P) JJ MacBrien (US DFC)

ROYAL CANADIAN AIR FORCE

426 TRANSPORT SQUADRON

- Not researched at this time

FIGHTER PILOTS

Combat Era (in order of participation in Korea)

- Flight Lieutenant O Levesque (1 MIG destroyed) (US AM, US DFC)

- Flying Officer B Fleming (D) (1 MiG probably destroyed, 2 damaged) (US DFC)

- Flight Lieutenant L Spurr (D) (1 MiG destroyed) (US DFC)

- Flying Officer G Nixon (US AM)

- Flying Officer J Donald

- Group Captain EB Hale (US DFC)

- Flight Lieutenant CA LaFrance (1 MiG Destroyed) (US DFC)

- Flight Lieutenant EA Glover (D) (3 MiGs destroyed. 3 damaged) (US DFC)

- Squadron Leader JD Lindsay (2 MiGs destroyed, 3 damaged) (US DFC)

- Flight Lieutenant RE Lowry (D) (US AM)

- Squadron Leader EG Smith (US AM)

- Wing Commander RTP Davidson (D) (US AM)

- Flying Officer A Lambros (2 MiGs damaged) (US AM)

- Flight Lieutenant AR MacKenzie (POW)

- Flight Lieutenant FW Evans (US AM)

- Flight Lieutenant GH Nichols (1 MiG probably destroyed) (US AM)

- Flight Lieutenant RD Carew (US AM)

- Squadron Leader J MacKay (1 MiG destroyed) (US AM)

- Squadron Leader WHF Bliss (US AM)

- Squadron Leader W Fox (US AM)

Post Cease Fire Era - (no combat missions)

- Flying Officer BJ Mullin

- Squadron Leader D Warren

OBSERVERS

NURING SISTERS

- Approximately 13 RCAF Nursing Sisters were involved in airlift activities during the Korean War. Names and

information not researched at this time.

SPECIALISTS

- Wing Commander ECR Likeness

- Group Captain KR Patrick

- Squadron Leader AJ Simpson

- Squadron Leader JT Reed (US Bronze Star)

TECHNICAL STAFF

- RCAF technical staff in Korea is not researched at this time.