History of the Squadron during World War II (Aircraft: Lancaster I, III)

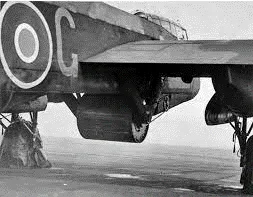

Arguably the most famous bomber squadron of the RAF, 617 Squadron was formed for the single purpose of attacking the major Dams in Germany using the UPKEEP “bouncing bomb - invented by the Vickers engineer Barnes Wallis (Later Sir Barnes). The squadron was formed on 21 March 1943, under the command of Wing Commander Guy Gibson DSO, DFC. Gibson had already a long history of wartime service, having completed two tours of operations on bombers and one on night fighters. He was given a free hand in selecting crews for the new squadron, and recruited a number of highly experienced pilots, although not all of the aircrew had a lot of operational experience. As soon as the squadron crews had assembled at their base at Scampton, Lincolnshire, UK ![]() , training for the operation (later given the code name Operation CHASTISE) started, although until the night of the operation itself the crews (except for Gibson himself) did not know what the targets would be. The raid was going to be almost unique in that the participating aircraft would be flying at about 60 feet (18.3 metres) over Germany on the way to the targets. Normally, bombers flew over Germany at heights above 15,000 feet (4600 metres), so the first priority of the training was to accustom the crews to flying at the extreme low level, first by day and then by night.

, training for the operation (later given the code name Operation CHASTISE) started, although until the night of the operation itself the crews (except for Gibson himself) did not know what the targets would be. The raid was going to be almost unique in that the participating aircraft would be flying at about 60 feet (18.3 metres) over Germany on the way to the targets. Normally, bombers flew over Germany at heights above 15,000 feet (4600 metres), so the first priority of the training was to accustom the crews to flying at the extreme low level, first by day and then by night.

Meantime, the weapon itself (UPKEEP) was being developed with great urgency from what was essentially a theory to a practical weapon: at the time when 617 squadron was inaugurated, the full-sized weapon had not been completely designed, nor had even prototypes been produced.

A Weapon to Destroy the Dams

The main centre of German heavy industry, the Ruhr, depended heavily on its water supply. This supply came mainly from the reservoirs behind two main dams: the Möhne and the Sorpe. To destroy the dams required that a large explosive charge be placed right against the dam face on the water side (explosions in the water further from the dam wall rapidly lose effect the further from the dam wall they are). But how was this precise accuracy to be achieved? A novel idea was put forward by Barnes Wallis, an engineer at Vickers aviation, that a bomb could be skipped along the surface of the water: he tested the feasibility of the idea first of all with marbles on a washtub full of water, then with golf-ball sized spheres, then with a half-scale model of the bomb that could be dropped from a

Essentially, the weapon and the squadron had the same time scale to be ready for the operation, which had to take place around the middle of May, because the dams needed to be attacked when the water was at its highest level. So there was great pressure on both the weapons designers and the airmen. Gibson himself attended some of the tests of UPKEEPs, many of which were failures because the bombs did not perform as was hoped. Eventually the problems were solved, and a final design could be defined and sufficient of the bombs could be manufactured in time for the raid.

After almost two months’ training for 617 squadron, Operation CHASTISE took place on the night of the 16/17 May 1943. Nineteen Lancaster bombers, specially modified to carry the UPKEEP bomb, participated, attacking 4 of the major dams in the Ruhr area. Of the participating aircrew, 26 of the 133 were Canadian, and one was an American serving in the RCAF. The operation was a success in that the Möhne ![]() and Eder

and Eder ![]() dams were breached (the Eder Dam was not in the Ruhr catchment area but was attacked because it was a good target for UPKEEP). The Sorpe dam

dams were breached (the Eder Dam was not in the Ruhr catchment area but was attacked because it was a good target for UPKEEP). The Sorpe dam ![]() was the third main objective, and was attacked by two crews and damaged, but not enough to form a breach: it was differently constructed from the Moehne and Eder dams and was less susceptible to being breached by UPKEEP. One aircraft attacked what is thought to be the Ennepe dam

was the third main objective, and was attacked by two crews and damaged, but not enough to form a breach: it was differently constructed from the Moehne and Eder dams and was less susceptible to being breached by UPKEEP. One aircraft attacked what is thought to be the Ennepe dam ![]() without result. Two of the attacking aircraft had to abort their missions. The water from the breached Möhne and Eder dams caused widespread destruction as the reservoirs emptied. Unfortunately for 617 squadron, the cost in killed aircrew was high. Of the 19 aircraft which set off on the operation, no fewer than eight were shot down or crashed: only 3 aircrew (1 of whom was Canadian) survived of the 56 (15 Canadians) who were in the missing aircraft.

without result. Two of the attacking aircraft had to abort their missions. The water from the breached Möhne and Eder dams caused widespread destruction as the reservoirs emptied. Unfortunately for 617 squadron, the cost in killed aircrew was high. Of the 19 aircraft which set off on the operation, no fewer than eight were shot down or crashed: only 3 aircrew (1 of whom was Canadian) survived of the 56 (15 Canadians) who were in the missing aircraft.

The operation catapulted 617 Squadron and its crews into the limelight: many of the airmen received decorations, starting with Gibson, who was awarded the Victoria Cross for his fortitude in leading the raid. However, it must be acknowledged that a loss rate of 42% for one operation, however successful, is not sustainable, and operations such as CHASTISE cannot be repeated: it was very much a one-off. Nevertheless, the operation was a great morale-booster for the British public.

There is a considerable literature on the Dams Raid, starting with Guy Gibson’s own description in his autobiographical account of life in Bomber Command (Enemy Coast Ahead – Uncensored, Crécy Publishing Ltd, 2003). Other more recent accounts of the raid and the events leading up to it are Dam Busters by James Holland (Bantam Press, 2012), Dam Busters by Ted Barris (Harper Collins, Toronto, 2018), and Chastise by Max Hastings (William Collins, London, 2019)

After the Dams Raid, a decision was made by Bomber Command that 617 would be retained as a specialist bombing unit, staffed by highly experienced aircrew, to undertake missions where precision bombing was required. However, after the Dams Raid, the squadron flew only a few operations to targets in Italy in July 1943, flying on to airfields in North Africa, and then attacking Italy again on the return to England. They also moved from Scampton, which was a grass airfield to Coningsby ![]() , which had hard runways, in August 1943. The squadron’s next major operation against Germany was on 15 September 1943. The objective was to make a low-level attack on the Dortmund-Ems Canal near Ladbergen, Germany

, which had hard runways, in August 1943. The squadron’s next major operation against Germany was on 15 September 1943. The objective was to make a low-level attack on the Dortmund-Ems Canal near Ladbergen, Germany ![]() . The squadron was tasked with dropping 12,000 lb high-capacity bombs into the canal so as to cause a breach. Unfortunately the operation was a disaster: the weather was poor and the target was heavily defended by flak. The canal was not breached and 5 out of the 8 Lancasters involved failed to return, including that of the CO, Wing Commander George Holden DSO, DFC & Bar, who took with him several of Gibson's original crew of the Dams Raid. Not surprisingly, after this operation, the squadron developed a reputation as a suicide unit and recruitment of fresh crews was difficult for a while.

. The squadron was tasked with dropping 12,000 lb high-capacity bombs into the canal so as to cause a breach. Unfortunately the operation was a disaster: the weather was poor and the target was heavily defended by flak. The canal was not breached and 5 out of the 8 Lancasters involved failed to return, including that of the CO, Wing Commander George Holden DSO, DFC & Bar, who took with him several of Gibson's original crew of the Dams Raid. Not surprisingly, after this operation, the squadron developed a reputation as a suicide unit and recruitment of fresh crews was difficult for a while.

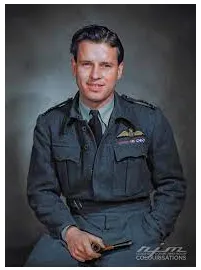

From this low point the squadron emerged as an effective special precision bombing unit. Under the command of Wing Commander Leonard Cheshire DSO and 2 Bars, DFC, they developed accurate target-marking techniques to go with their precision attacks. Initially, they attacked using conventional bombs, but later they were the first squadron to use the 12,000 lb "Tallboy" bomb, another of Barnes Wallis’s designs, which had to be accurately delivered on

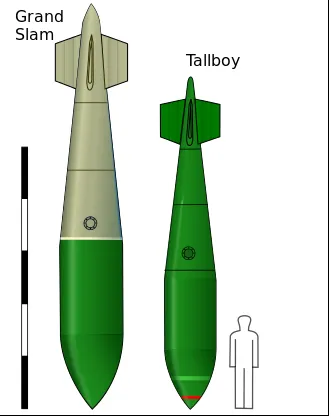

specific targets rather than being used in the area bombing of German cities. To achieve maximum accuracy the squadron was given the Stabilising Automatic Bomb Sight (SABS). They were the only squadron to use this sight in preference to the standard Mk. XIV bomb sight used throughout Bomber Command. Only one other squadron in Bomber Command (9 Sqn) was trained to drop the Tallboy bomb, and they frequently accompanied 617 on its operations. Later, when an up-scaled 22000-lb version of the Tallboy was developed (the Grand Slam), 617 was the only squadron to use this weapon, using highly modified Lancaster aircraft to carry it.

Before using these weapons, the squadron moved again to nearby Woodhall Spa ![]() in January 1944, and they remained there for the rest of WWII.

in January 1944, and they remained there for the rest of WWII.

Tallboy and Grand Slam Earthquake Bombs

Bomber Command in WWII faced several problems in its area attacks on axis targets. Among them were the difficulty of aiming bombs which had poor aerodynamic properties. The high-capacity explosive bombs (4,000, 8,000 and 12,000 lb) were more or less simple thin-case steel cylinders packed with explosive. Therefore in their journey to the ground they did not follow the path of a fully aerodynamic bomb: they wobbled about and thus could not be aimed with precision. Nor could they penetrate into the earth: air-raid shelters with only a fairly thin skin of concrete could resist the blast. On the other hand, the smaller medium-capacity (1,000 and 2,000 lb) bombs were more aerodynamic and could be aimed more precisely, but they were not heavy enough to penetrate deeply into earth, and could hardy dent concrete. As a result of these failings many conventional bombs were expended uselessly attacking the U-boat pens at the French ports, which were protected by several feet of concrete. For night-time area bombing raids on cities these drawbacks did not greatly matter. When, however, it was a question of hitting and destroying solidly-built precision targets it was clear that other weapons were required.

The ever-fertile brain of Barnes Wallis had early on in the conflict considered how bombs could be made more effective: the principle that he worked on was that if a sufficiently heavy bomb could be dropped to penetrate deeply into the earth before exploding, a local earthquake would be created, which would destroy structures from below, by causing an underground cavity (camouflet) into which the structure would collapse. Ideally, for this to happen the bomb would just miss the target rather than hitting it directly. So to destroy precision targets, a bomb would be required (i) that was heavy enough to penetrate the earth deeply; (ii) that was strong enough to resist the impact when it hit the ground; (iii) which carried a large explosive charge: and (iv) which could be aimed with precision. Originally, Wallis had suggested a 10-ton weapon, but there was at the time no aircraft capable of carrying it, and Wallis’s proposal to design a bomber capable of doing so was not accepted: at the time (early 1940s) the pressures on the British aircraft industry would not allow for the

Meanwhile, work was continuing on the full-scale 22,000 lb (10,000 kg) bomb, which was named the Grand Slam. It was 26 feet 6 inches (8.08 m) in length with a diameter of 3 feet 10 inches (1.17 m) and carried an explosive charge of 9,500 lb (4,309 kg) of Torpex D1. Like the Tallboy, its head was of specially

On the night of 5 June 1944, the squadron was part of an important "spoof" operation, which used their navigational skills rather than accuracy of bombing. The operation (TAXABLE) was intended to draw the German attention away from the landing beaches for D-Day, in Normandy, France, by giving the impression of a convoy of ships heading towards the Pas de Calais region of France. This was achieved by precision flying, combined with dropping "Window" (aluminized paper strips to confuse the German radar) at precise intervals. This gave to the German radar operators the impression of a convoy sailing at a speed of 5 knots. This ruse seems to have been successful, in that the German High Command retained considerable forces in the Pas de Calais area rather than re-routing them to the true invasion area.

Once they became available, Tallboys were used in many critical attacks by 617 squadron. One of the most important, and the first use of the Tallboy, was the precision bombing of the Saumur railway tunnel in France on 8 June 1944. The destruction of the tunnel and the railway prevented German reinforcements from arriving rapidly in Normandy to counter the D-Day landings. From then on, the squadron increasingly used its Tallboys to attack V-weapons launching and storage sites, and the U-boat and E-boat pens at French and Dutch ports: previously the thick concrete roofs of these structures had been immune to conventional bombs.

On July 4, 1944, Wing Commander Cheshire completed his one-hundredth operation and was immediately taken off operational flying and was the second member of 617 Squadron to be honoured with a Victoria Cross, not for any particular act of valour, but for his continued courage throughout his operational career. He was replaced by Wing Commander Willie Tait, who also had more than 100 operations to his credit, with a DSO and DFC & Bar.

Apart from the Dams raid, the best-known operations of 617 and 9 Squadrons were the raids on the German battleshipTirpitz. In September 1944, the ship was based at Alten Fjiord in the far north of Norway ![]() , too far from Britain for the Lancasters to make a round trip. It was therefore arranged to fly first to an air base in the USSR (Yagodnik

, too far from Britain for the Lancasters to make a round trip. It was therefore arranged to fly first to an air base in the USSR (Yagodnik ![]() ), and to attack the Tirpitz from there, return to Yagodnik and then return to the UK (Operation PARAVANE). The operation was performed, and enjoyed success, although it was not realized at the time. Despite the smoke screen that protected the battleship, one Tallboy bomb hit the ship, disabling it: but it was not sunk. It was subsequently towed to Tromso Fjord

), and to attack the Tirpitz from there, return to Yagodnik and then return to the UK (Operation PARAVANE). The operation was performed, and enjoyed success, although it was not realized at the time. Despite the smoke screen that protected the battleship, one Tallboy bomb hit the ship, disabling it: but it was not sunk. It was subsequently towed to Tromso Fjord ![]() to be used as a static defence battery, but by this movement it came just within range of British-based Lancasters. Wing Commander Tait led Nos. 617 and 9 Squadrons out from the north-east Scotland air base at Lossiemouth

to be used as a static defence battery, but by this movement it came just within range of British-based Lancasters. Wing Commander Tait led Nos. 617 and 9 Squadrons out from the north-east Scotland air base at Lossiemouth

![]() on October 29, 1944 (Operation OBVIATE).

on October 29, 1944 (Operation OBVIATE).

In December 1944, Wing Commander Tait, who was by now the possessor of DSO & 3 Bars, DFC & Bar, was taken off operations and was succeeded by Wing Commander J. "Johnnie" Fauquier, RCAF, DSO & Bar, DFC, who had flown extensively before the war before joining the RCAF, where he had commanded No. 405 Vancouver Squadron. He commanded 617 Squadron until the end of hostilities, where they continued to hit pin-point targets. The most noteworthy happening in this period was the arrival of the first 22,000 lb (10,000 kg) Grand Slam bombs. They were the biggest and most powerful bombs to be dropped in WWII, until the USAAF's use of nuclear bombs against Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. They required specially modified Lancasters to carry them, with extra powerful Merlin engines and all excess weight removed from the aircraft. The first Grand Slam was successfully dropped on the Bielefeld railway viaduct on March 14, 1945, by Squadron Leader C.C. "Jock" Calder, DSO & Bar. The squadron dropped 42 Grand Slams in the course of March-April 1945. The final operation of 617 Squadron in WWII was the attack on "Hitler's Lair" at Berchtesgaden on 25 April 1944. Similarly to the previous leaders of 617 Squadron, Group Captain Fauquier was taken off operational flying just before this raid. He was succeeded by Wing Commander J.E. Grindon.

As a postscript to the activities of 617 Squadron 1943-45, it may be appropriate to quote the author Paul Brickhill in his book The Dam Busters. "if 617's bombing seems monotonously "dead-eye", remember that they dropped [their bombs] at nearly 200 mph, 18,000 feet up and several miles back. And they were of course "dumb" bombs: once they were dropped, they could not be guided. Nevertheless, 617 Squadron had an average error of less than 100 yards in their dropping of the earthquake bombs.