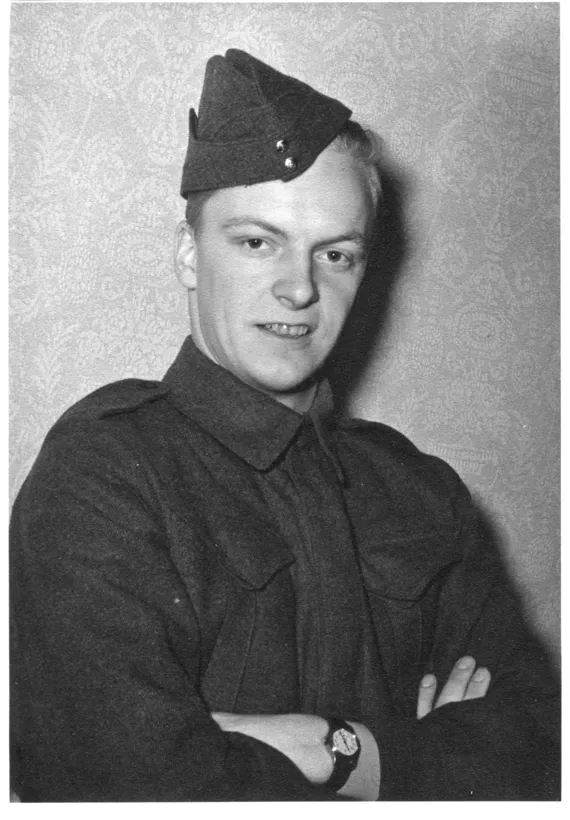

A. Ross Dawson, COTC, March 1941, A.R Dawson Collection, courtesy CWM

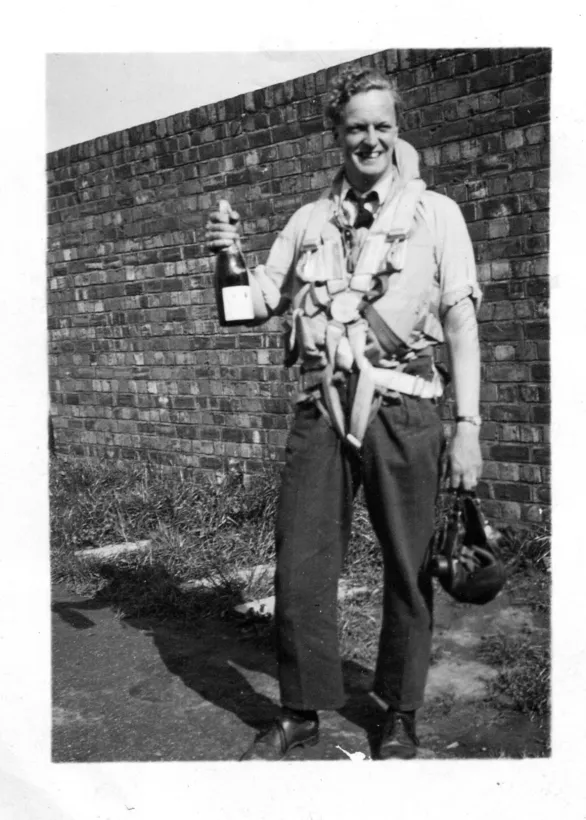

Squadron Leader A. Ross Dawson, VE Day 1945-05-09 A.R Dawson Collection, courtesy CWM

Flying Officer A Ross Dawson with Bolingbroke, Fingal 1942, A.R Dawson Collection, courtesy CWM

Flying Officer A Ross Dawson (centre) 1945-03-20, A.R Dawson Collection, courtesy CWM

Squadron Leader A. Ross Dawson was a Engineering Technical Officer with the RCAF from January 1942 to June 1945. During his time overseas, from 1943 to 1945, he kept a diary of daily life and events on various RCAF Group 6 Bomber Command airfields in Yorkshire UK. As a Technical Officer, as well as taking on the stressful daily grind of getting aircraft serviceable for operations, he was also involved in doing forensic assessment of aircraft crashes. His diary, which extends to 460 hand written pages, includes numerous accounts of specific crashes, missing aircraft and crew losses. Many of his first-person accounts of these incidents are included in the CASPIR data base referencing aircraft serial numbers and named personnel as listed in the link here.

List of Squadron Leader A Ross Dawson Diary Transcripts in CASPIR

List of Squadron Leader A Ross Dawson Diary Transcripts in CASPIR

The original diaries, photographs and related technical material are in the A. R Dawson collection of the Canadian War Museum and a full set of the scanned diaries are provided here courtesy of the CWM.

Squadron Leader A Ross Dawson Synopsis of his Diary A.R Dawson Collection, courtesy CWM

Squadron Leader A Ross Dawson Synopsis of his Diary A.R Dawson Collection, courtesy CWM

Squadron Leader A Ross Dawson Diary Jan 16th 43 to May 31st 43 A.R Dawson Collection, courtesy CWM

Squadron Leader A Ross Dawson Diary Jan 16th 43 to May 31st 43 A.R Dawson Collection, courtesy CWM

Squadron Leader A Ross Dawson Diary May 31st 43 to Sept 27th 43 A.R Dawson Collection, courtesy CWM

Squadron Leader A Ross Dawson Diary May 31st 43 to Sept 27th 43 A.R Dawson Collection, courtesy CWM

Squadron Leader A Ross Dawson Diary Sept 27th 43 to Jan 31st 44 A.R Dawson Collection, courtesy CWM

Squadron Leader A Ross Dawson Diary Sept 27th 43 to Jan 31st 44 A.R Dawson Collection, courtesy CWM

Squadron Leader A Ross Dawson Diary Jan 31st 44 to July 10th 44 A.R Dawson Collection, courtesy CWM

Squadron Leader A Ross Dawson Diary Jan 31st 44 to July 10th 44 A.R Dawson Collection, courtesy CWM

Squadron Leader A Ross Dawson Diary July 10th 44 to Oct 26th 44 A.R Dawson Collection, courtesy CWM

Squadron Leader A Ross Dawson Diary July 10th 44 to Oct 26th 44 A.R Dawson Collection, courtesy CWM

Squadron Leader A Ross Dawson Diary Oct 26th 44 to April 20th 45 A.R Dawson Collection, courtesy CWM

Squadron Leader A Ross Dawson Diary Oct 26th 44 to April 20th 45 A.R Dawson Collection, courtesy CWM

Squadron Leader A Ross Dawson Diary April 21st 45 to June 23rd 45 A.R Dawson Collection, courtesy CWM

Squadron Leader A Ross Dawson Diary April 21st 45 to June 23rd 45 A.R Dawson Collection, courtesy CWM

Squadron Leader A. Ross Dawson MBE (click to go to section)

Flying Kites in Yorkshire

This is a summary of the story A. Ross Dawson tells in his wartime diary, supplemented by technical material he retained, and family records. It has been prepared by his son W.R. (Bill) Dawson in January 2024. In the first week of arriving at his first UK posting at Leeming, Yorkshire, Ross began to refer to their aircraft as 'kites' and did so consistently throughout the remainder of his time overseas.

Pre War Life

Alexander Ross Dawson was born in Toronto on December 23, 1918 and grew up in the rough-and-tumble east-end Greenwood area as part of a close-knit extended family. Unfortunately, in 1933, in the midst of the Depression, his father died and at age 14, and he became the 'man of the house' for his sister and mother. Finances for the family were difficult but he excelled at school and through scholarships and family support he was able to study Mechanical Engineering at the University of Toronto. On graduation in 1940 he joined the Canadian Officers Training Corps (COTC) and turned down an offer to undertake a Masters degree at MIT in Boston.

In the fall of 1941 he enlisted in the RCAF to train as a pilot but, almost immediately, when the Commanding Officer found out the Ross was a qualified Mechanical Engineer, he was reassigned to the Aeronautical Engineering Branch. Apparently they had many candidates hoping to become pilots or aircrew but had very few qualified engineers. This very reasonable change had long term implications for Ross. In particular it set the stage for Ross to experience a degree of survivor guilt as, in the coming years, he would lose many friends and acquaintance who had become aircrew while he was 'stuck on the ground'.

Aeronautical Engineering School (AES) and Bombing and Gunnery School #4 Fingal

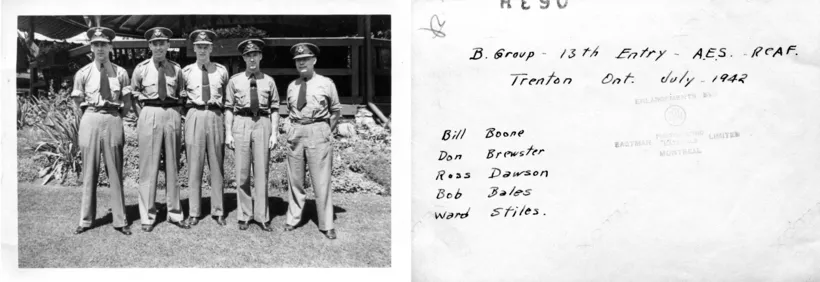

13th Entry AES RCAF B-Group Trenton July 1942

Crash of Bolingbroke 9133 1942-07-12 Fingal

In the spring of 1942 Ross completed a 22-week intensive course at the RCAF Aeronautical Engineering School (AES) in Montreal, along with 18 other candidates in the 13th entry to the school. He would remain close friends with a number of his fellow students throughout the war. On completion of the Aero course, Ross was assigned to the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan's No. 4 Bombing & Gunnery School (B&G) at Fingal, Ontario. The work involved maintaining a range of training aircraft including Lysanders, Fairey Battles, Ansons, and Bolingbrokes and, infrequently, a Hampden or Harvard.

He began at B&G Fingal the first week of July 1942, first as a day-time flight officer, then as the flight officer in charge of night operations. By September he was acting O/C (Officer in Charge) of the Service Squadron with 105 men reporting to him. His rapid advancement reflected his developing skills as an operations manager and a desperate lack of qualified people to undertake these roles in the RCAF. This would be the pattern for much of his career with the RCAF over the coming years. His promotion from Pilot Officer to Flying Officer came through in July, shortly before he took on an acting position that would typically be filled by the next rank up, Flight Lieutenant.

Part of Ross's job was to investigate aircraft crashes to determine if there was an equipment or maintenance issue involved. He investigated and recorded a number of relatively minor crashes at Fingal and the experience was valuable in preparing him for frequently having to undertake the same task overseas.

Note on Crash Categories

Ross Dawson's Notes on Crash Categories

During WWII in Britian the RCAF field operations adopted the standard RAF categories for aircraft damage which are reversed from the Aircraft Damage Level (ADL) currently used by the RCAF and generally in the CASPIR Database. Squadron Leader Dawson used the RAF classifications extensively throughout his diary. His personal reference notebook lists the categories as shown.

The current RCAF Aircraft Damage Level categories are:

- Category A - Destroyed/missing; Aircraft normally written off the inventory;

- Category B - Very serious; The aircraft has sustained damage to multiple major components;

- Category C - Serious; The aircraft has sustained damage to a major component;

- Category D - Minor; The aircraft has sustained damage to non-major components;

- Category E -Nil; The aircraft, including the power plant, has not been damaged:

North Atlantic February 1943

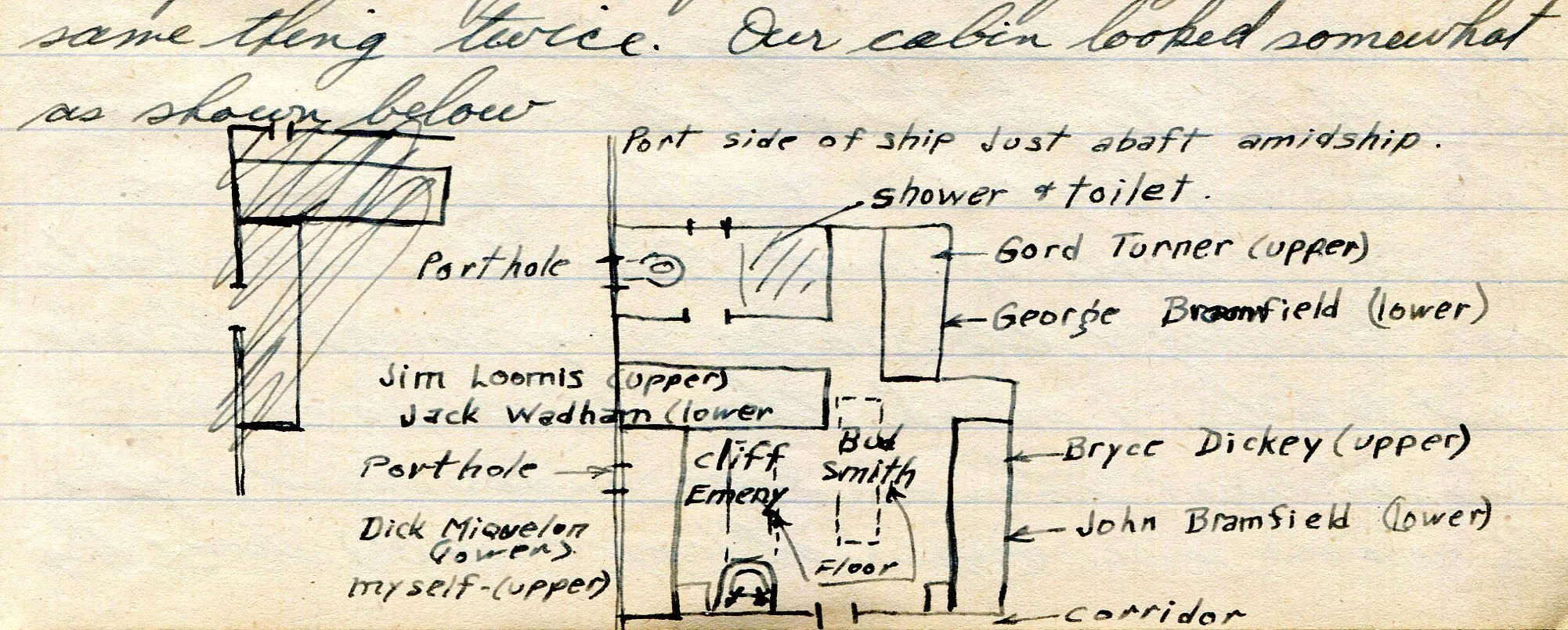

Bunk Layout on the Empress of Scotland 1943-02

In December 1942 Ross was posted to Group 6 Bomber Command in the UK and travelled to Halifax, Nova Scotia, on January 16, 1943, which was the day he began his daily diary. They boarded the Empress of Scotland (formerly the Empress of Japan, renamed in the eight weeks since Pearl Harbour) and Ross was in room 149 on B Deck. There were ten officers assigned to a room normally used for two. There were only four double bunks so two people were assigned to sleep on the floor.

'It is not too bad except for lack of space to store luggage and move around in . . . also rigged up ropes all over the place for hanging up clothes etc.' To add to the general discomfort, they were under strict orders to sleep in their clothes while on board so Ross did not change some of his clothes for the next 10 days.

They departed Halifax harbour February 5 at 0400 hrs into 'a terrific gale and the sea is very rough . . . the waves are very high (approx. 40 feet) since they are often up level with us when standing on the top deck. . . There are plenty of fellows seasick already and it is getting worse all the time. I really feel sorry for the airmen and army troops below decks in their crowded dormitories with no place to lie down etc. - they sleep in hammocks that are slung at night only. As a matter of fact, I feel a little squeamish myself and didn't like the look of the greasy bacon and fried eggs for breakfast. . . By 6:00 pm I was still feeling poor and could only go for some chicken soup, bread and tea but this was more than a lot of fellows did since more than half the places were vacant and about half of those present got up suddenly at dinner and hurried outside.

By Sunday, February 7 they were in danger of attack by German submarines and began 4-hour lookout watches. The Empress of Scotland was a fairly fast cruiser with a top speed of 22 knots so could outrun submarines. For this reason, they sailed on their own without a convoy: the danger lay in submarines lying in wait for them as they passed. The weather had improved with calmer seas so that 'the only roll we get is when the ship changes course every 5 minutes and we heel way over - they travel a constant zig-zag course. Their course took them far to the south, only a few hundred miles above the equator - quite a round-about way to get to England.'

Heading north again into cold, rougher seas, their time was spent on submarine watch. The risk of submarine attack increased as they approached the UK, and on Wednesday the submarine lookouts were doubled as an aircraft patrol attacked a wolf pack of submarines 40 miles ahead.'We spent all day cruising up and down the North Atlantic not far from Ireland but not going ahead. Word is that we are going to make a fast run tonight through the sub-infested waters. . . . We also have to watch for enemy a/c now as well as submarines. Bob and Bill both still sick and Bob hasn't eaten for two days - he sure looks bad. Increasingly windier and rougher tonight.'

Ross's 8:00 am submarine watch on Thursday morning began in darkness. 'I hadn't been there for more than half an hour when I first saw a light winking faintly on our starboard bow - good old Northern Ireland! Another half hour and there is another on the port bow - Scotland! We made it at last. As it gradually got lighter, we came quite close to Ireland and it sure looked pretty in the early morning sunlight with the haze just lifting away from the shore and revealing the light green hills and valleys . . . Ireland fades as we enter the Firth of Clyde . . .and we all sing Roamin in the gloamin by the bonnie banks of the Clyde. . . . At 2:00 pm we anchored at Gourock . . . 6 and a half days since we pulled out of Halifax.'

Finally, on Saturday they disembarked by tender at 4:00 pm and by 4:30 pm sharp were 'on one of those cute little English trains, small but fast and streamlined', heading for the south coast of England. A cramped and sleepless 18 hours later they arrived in Bournemouth.

HCU 1659, 1664 and 427 Squadron - February to December 1943

When Ross arrived in Bournemouth on February 13, 1943, the extensive hotel facilities of the resort town had been taken over as the Personnel Reception Centre for the RCAF in Britain. Over five thousand RCAF personnel were temporarily in residence while being processed and posted. While aircrews were often stuck in Bournemouth for up to 3 months, the engineers were in great demand and were processed quickly. Four days after Ross arrived in Bournemouth, Senior Aero Engineer Squadron Leader R. J. Brearley came down from London to meet with Ross and eight other engineers. Three weeks after arriving in Britain, including a week off, Ross arrived at his posting to 1659 Heavy Conversion Unit (HCU) at Leeming, Yorkshire, on March 1, 1943.

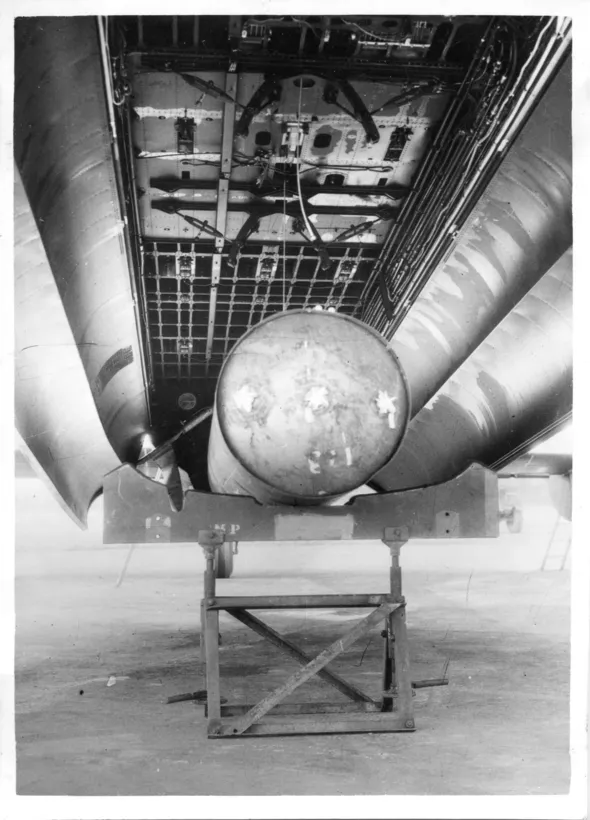

2000 pdr - bomb bay of Halifax II Leeming 1943

Replacing propellers - Leeming 1943

Ross's prized motorbike at Croft

Billetted in a Nissan Hut

The conversion unit was converting 408 Squadron from Wellington to Halifax bombers. Ross would spend most of the next 18 months working with, and starting up new HCUs. And so began a daily grind of servicing training aircraft and hearing from operational aircrews about on-going bombing operations

On March 10, ten days after his arrival in Leeming, he witnessed a horrendous crash that left an indelible impression. 'Well up until today everything has been quite rosy but this afternoon I witnessed one of the most appalling sights I ever hope to see & I'm sure I will never forget it as long as I live.' One of his aircraft, Wellington W1241, B Flight - Q for Queenie, with eight Canadians on board, crashed into a field close to the aerodrome and 'the whole thing was a seething mass of flames.' There were no survivors.

in May, a new HCU, HCU 1664, was being formed and Ross was assigned to start it up. 1664 HCU would be based at Croft aerodrome about 20 miles north of Topcliffe. This also meant a promotion to Flight Lieutenant and would be the first time he would be in sole command of a unit. 'It is a brand new unit starting from scratch and it is actually still in the process of construction. The mess is very small & there are about 12 officers here. . .. Our living quarters are in these little half cylindrical Nissan huts. . . .There are electric lights but no running water & outside two-holers. . . . It rained all day today & things are certainly a mess. . . contractors are still digging all over the place . . . I just about ruined my shoes and battle dress splashing around through the muck. . . It is certainly going to be valuable experience to me in starting up our complicated Servicing and Maintenance organization with nothing whatsoever to start with. There are about 130 of our men wandering around doing nothing. There is no equipment here at all yet but there are 5 Mk V Halifax a/c just standing here waiting for acceptance checks'.

The second day they were at Croft it snowed,'leaving a thick coating of muddy slush over everything . . .we haven't even got paper to write on & not a single useful piece of equipment has arrived yet. It is very discouraging but somehow or other I like it when the going is tough.' The day following, 'I took a transport & went on a scrounging trip to Topcliffe & Leeming to get some spare mods, paper forms & stationary etc. & it was quite successful since everyone seemed to be quite anxious to help us get started. . . . .I finally got a pair of knee-high rubber boots to wade around in . . . . The hard part to arrange is the maintenance & servicing especially where there is only one small, flimsy tin hanger built like a barn with no lean-to offices or nothing. I guess I'm going to have to operate my flight from an open-air dispersal until the other hanger is built. It will be pretty tough but I guess we can do it if we can only get our ground equipment in.'

In his diary Ross relates numerous anecdotes about aircraft incidents, some humorous, some gruesome, interspersed with personal anecdotes about days off, evenings out and periodic leave. It is an intense time.

On August 3, 1943, hoping for an early night before a day off, 'Bill Tait, my Scotch friend came barging in saying a kite was bogged down in the mud near D flight, was blocking the runway & Flying Control wanted it out as soon as possible. That really fixed it so I got dressed & went out in the pitch black night which didn't help much. I commandeered a light van & went careening around in the dark looking for stuff to help lift the kite out. I got a jack and pad from the contractor's cat AC kite in the hanger, broke in to Servicing Flight stores for a spanner and swiped B flight's tractor & finally got the kite out at 3:30am. Then we went up and had an aircrew meal of bacon and eggs at the Sergeant's mess and went back to bed.

Rest and Relaxation

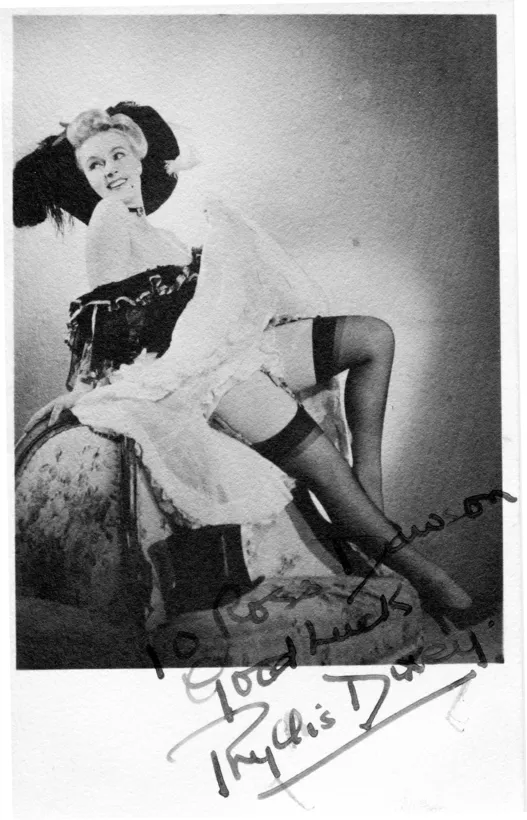

Phyllis Dixie Review Program

While there were long hours of stressfull activity, there were also much needed breaks from the action. Ross recounts stories of carousing at the Officer's mess and local pubs, parties and dances, and a number of girlfriends during his time overseas. But the war was never far from mind. In one case a party on the aerodrome was interrupted by a serious crash that Ross had to investigate (see DG282 1943-12-02).

He went on weekend and one-week leave a number of times when he had a chance to explore. On July 1, 1944, Ross wrote, 'Got a transport to take us down to York to catch the London train . . . arriving at Kings Cross station about 2:30. The train had just stopped & we were getting out of the carriage when the first air-raid siren went - more buzz-bombs. Nobody seemed to pay much attention & went about their business normally although quite a few people were seen to make for the subways'. They got to their hotel around 4:00 pm. 'In the meantime there were about three more alerts & four or five more bombs went off with a dull crump somewhere in the city. We then decided to go to a stage show & went to see Phyllis Dixie in a good musical review. There were still air raids going on about every half hour. When we came out we were standing talking to the hat check girl in the lobby. . . a buzz bomb suddenly fell about 200 yds down the street just back of Big Ben with quite a loud explosion. The hat check girl was very nervous & grabbed hold of Rip with a real look of terror in her eyes. I guess it must be hard to take after so long.'

Later that evening, 'at 11:30 we went down to the Victoria embankment and stood near Westminster Bridge practically in the shadow of Big Ben & Waterloo Bridge looming up on our left. The city noises had quieted down & we figured we could maybe see some of the buzz bombs. After about ten minutes an alarm went off and in another 5 minutes came the explosion. Then there were two or three others in quick succession & finally we heard one coming over very low. The motor has a peculiar throbbing sound which is unmistakable. It was very low cloud base so we couldn't see anything but we could sure hear it. The motors got louder & louder until it was directly overhead & the motors cut out suddenly & there was dead silence. This is the most uncomfortable time in the six seconds or so waiting for it to hit. Suddenly there was a blinding flash right in front of us & a great explosion causing us to both duck to the pavement behind the nice thick embankment wall. It hit a building just across the Thames from us.'

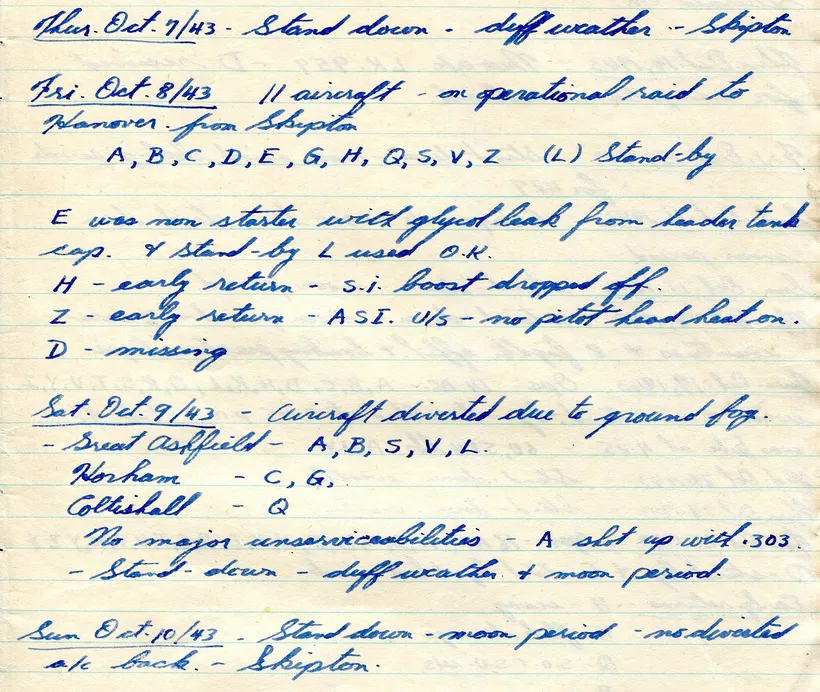

427 Daily Ops Notebook - October 1943

Ross heard the news on October 4, 1943, that he was posted to 427 Squadron in Leeming with W/C Turnbull as CO. This was the first posting where he was responsible for day-to-day bombing operations, with higher expectations of delivering fully serviceable aircraft on demand in a very dynamic environment of changing timing and targets, and brutal weather conditions. However, the posting would only last a few weeks.

HCU 1666 and 1679, Wombleton - December 1943 to July 1944

In late November Ross 'found out that I am to be posted to Wombleton soon to fill the Squadron Leader vacancy there which sounds all right even though it is to be a combined Halifax and Lancaster Conversion unit. I'll be first of all the lads that came over with me to get a chance like this . . . now if I can only hold down the job successfully, I should be OK.'

Ross arrived at the brand new station of Wombleton on December 11, 1943, pleased about the possible promotion to Squadron Leader but unhappy both about going back to a HCU and going to Wombleton ' way out in the wilderness. . . This is going to be one of the toughest jobs to handle with 16 Halifax V's with Merlin engines & 14 Lancasters with Hercules engines - the only unit in the group with two types of aircraft to handle.'

In contrast to the nearly chaotic activities in daily operations in Leeming, the predictable grind of HCU operations was now familiar to Ross and his diary entries during his time at HCU 1666 typically make only brief comments along the lines of 'flew hard all day today . . was on the go all day today.' Most of the longer entries describe what he did in his free time with periodic references to abnormal events.

On June 12 Ross found out that 'this post I have been filling here has been increased to a W/C vacancy & they are posting in a brand new sprog Canadian W/C to be under training under me for a while & then take over my place. What a break - the hard work is all done now & things are well organized & coasting smoothly along without much trouble so somebody else takes over. Everyone from the G/C down feels it is sort of a dirty trick but on the other hand, I am so junior as a Squadron Leader that I couldn't expect much else. I don't mind not getting my W/C out of it so much as I do the fact that I'll have to leave here just as I was on easy street & beginning to enjoy it - it is a swell station. As it stands now, I am posted to No 6 Grp. H.Q. & gosh knows what that means. I think I'll get after the G/C to see if he can't pull a few strings and get me back on to an operational squadron again - at least it is exciting'

6 Group HQ, Allerton Hall - July, August 1944

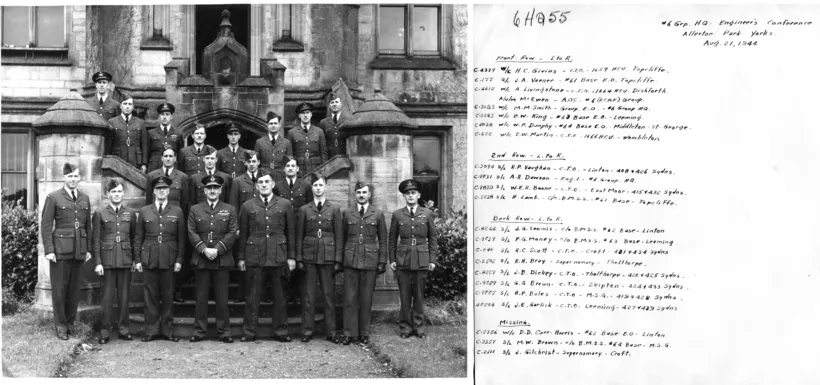

Grp 6 Engineering Conference August 1944

Ross reported for duty at Group 6 HQ in Allerton Hall on July 17, 1944. He was 'back in another Nissan hut again. Met lots of old pals here so I won't be a stranger at all. . . Ready for work under W/C Smith as Vice Group Engineering Officer & also in charge of Eng 1 which is the statistical analysis of all operational failures & engine & airframe troubles, crashes etc. Spent a very quiet day reading . . .I sure won't be overworked by the look of things which somehow doesn't appeal to me much. .. The poor old conversion units are practically forgotten down here. . . . it is much easier than looking after my wing at Wombleton - the only difference being that the stakes are higher & responsibility much greater with 14 operational squadrons and 3 con units to worry about.'

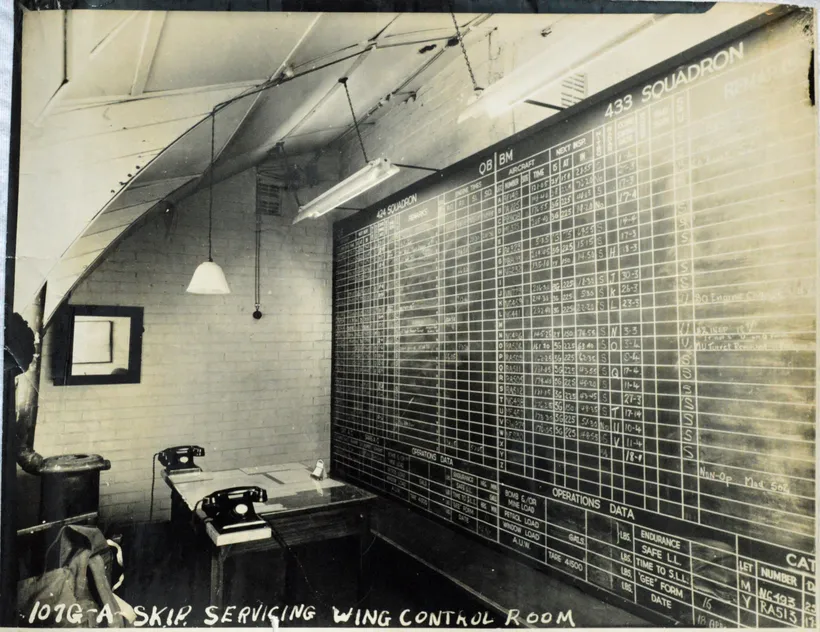

Ross was anxious to return to operations however, and he didn't have to wait long. On Monday, September 4, 1944, W/C Smith returned briefly from leave specifically to tell Ross he had a new commission: '424 & 433 squadrons . . . at Skipton-on-Swale were the two worst squadrons in the group last month. Had more accidents, crashes & operational failures than any others, so I am posted there as CTO [Chief Technical Officer]'

424/433 Squadrons, Skipton-on-Swale - August 1944 to February 1945

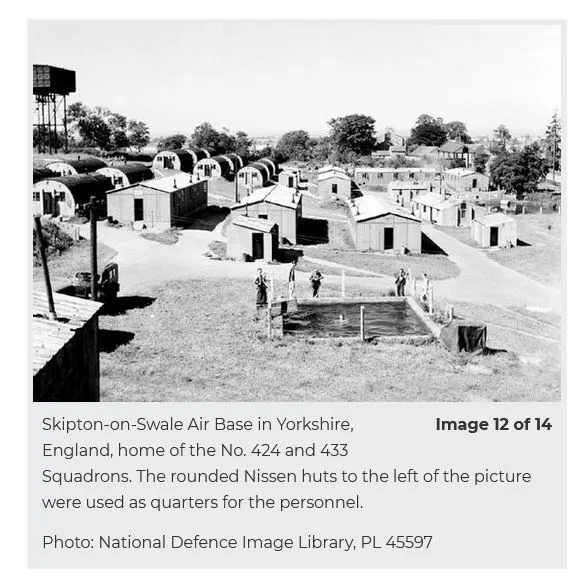

Skipton-on-swale airphoto

Royal visit to Linton 1944-08

On August 10, 1944 Ross attended a Royal visit to Linton Aerodrome where 'the King, Queen & Princess arrived by car . . . Several times I was right beside them & watched them & heard them talk & got a smile from the Queen at one time too, so it was all very interesting. . . The King looked very jovial . . . the Queen looked nice as ever, but everyone was amazed at how pretty Princess Elizabeth was - she is really very pretty'

On September 6, 1944, Ross 'went on to Skipton this afternoon in the pouring rain . . . Was very wet and cold tonight, slept in the spare room tonight with no sheets on the bed - cold and miserable. Another winter in these Nissan huts is going to be tough. Skipton is very much like Wombleton but not so well organised - yet. Batmen & hot water are nil & living conditions are pretty terrible.'

There were two operational squadrons stationed at Skipton-on-Swale aerodrome with a roster of 25 aircraft each and Ross was the Chief Technical Officer for both squadrons. This involved keeping as many of the aircraft as possible available for operations and the supervision of 1,500 maintenance and servicing staff.

He very quickly fell back into the intense daily routine, with 15 operations in his first month back. His focus initially was 'to get some semblance of organization around here.'

The Notebook

On arrival at Skipton Ross began keeping a Daily Operations notebook.

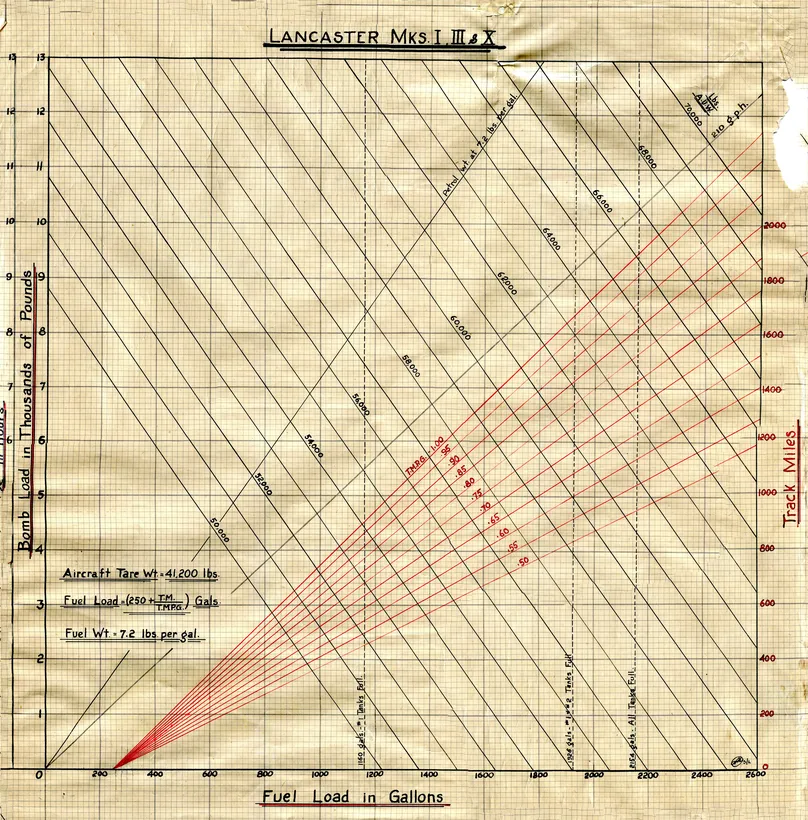

Fuel, Distance and Bomb Load Chart - Drawn by Ross

Example of Daily Operations notebook - November 4 1944

As shown in the example, each day had a two page spread and included a list of individual aircraft available for the operation, with a check mark when they took-off. It also included the information needed to calculate petrol and bomb loads based on the required 'endurance' hours to reach the planned target and return. In addition to ensuring that the take-off proceeded smoothly, he also monitored their return to base hours later. He recorded the outcome of the operation for individual aircraft; in this case two aircraft are reported missing, one aircraft has major flak damage that resulted in it being written off (Cat E), one aircraft landed at another aerodrome because of low fuel, and two aircraft arrived back later than expected.

Ross's time at Skipton was one of unrelenting operations. He was running operations there for 185 days, and on 132 of those days servicing crews had to fuel and bomb-load aircraft, frequently multiple times due to changing orders. They actually operated 89 days and 43 days operations were scrubbed on the day - but from a ground-crew perspective there was no difference. There were 37 days when ops were cancelled because of poor weather which left 16 days which Ross does not account for in his diary. Some of these will have been nights with full moons when night bombing was suspended. Interspersed in this time they took a month to convert the Squadrons from Halifaxes to Lancaster I and III bombers, requiring extensive training and test flights. Ross did manage two leaves, a 7 day and a 10 day, but otherwise he was on 24 hour call and frequently had to work through the night.

The bombing strategy had moved on to daylight sorties which was both good and bad from Ross' perspective. 'These daylight ops are sure different from the night sorties we used to do when I was with 427 Sqdn. since we rarely lose any kites these days - nearly a year ago we lost anywhere up to four a night. However, there are still plenty of flak holes etc. to patch up.' However daytime operations meant that ground crews often had to work overnight and Ross worked long hours with little sleep.

The big news in January 1945 was that they were getting to replace 'our Halifaxes with Lancaster I's and III's & it's going to be quite a major job but after we do convert we sure will be able to carry some hefty bomb loads.' January 28 was, in fact, the final time the squadron operated with Halifax bombers - all further operations were exclusively with Lancasters. Ross notes, 'What a bomb load they can take! Up to 15000 lbs where the Hali wouldn't take over 11,500 & also travel 2000 miles in the bargain with a full load of 2154 gals of petrol which sure beats out the old Halifaxes.'

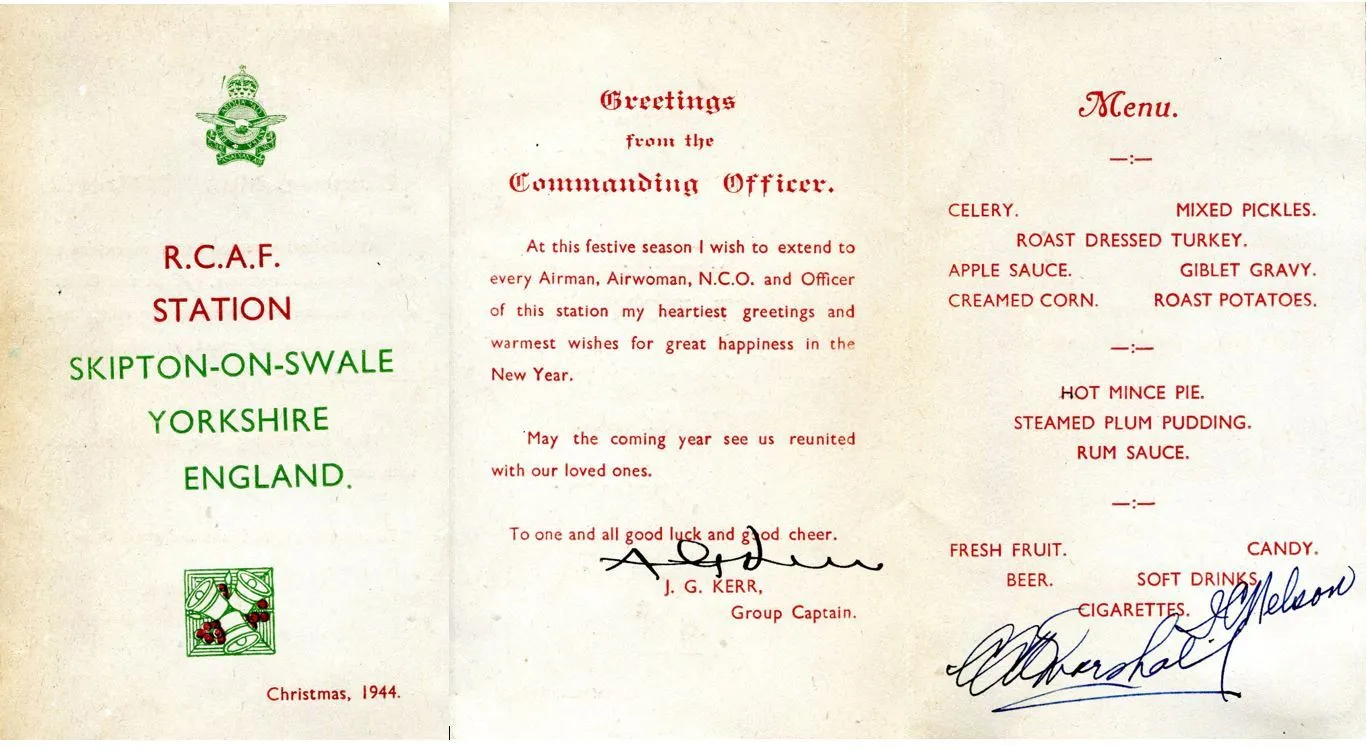

Christmas Dinner 1944

Christmas Dinner menu - November 4 1944

There was some relief on Christmas Day 'When word came through that there were no ops this morning I gave all my boys a stand-down & then gave myself a Christmas present & slept until noon. . . went to a nice turkey dinner with all the trimmings including plum pudding with rum sauce, It was very good too although not quite the same as being able to carve off as much turkey for myself as I wanted. At night we proceeded to have another big party in our new bar, then the G/C & I went down to visit the Sergeants Mess & from there to a dance being held in the NAAFI. From there I staggered home to bed.'

Ross Dawson's MBE Story, Skipton-on-Swale - January 28, 1945

Crash of LW164 1945-01-28 Skipton

Ross believed that it was the following event that resulted in his being awarded an MBE.

July 28, 1945: 'Well, we had quite an exciting day (and tragic too) as seems to happen quite frequently on Sundays. We got 8 a/c from 424 & 6 from 433 all ready to go on an op to Stuttgart. The bomb load 1 - 2000 pounder plus 12 - 500 lb clusters of incendiaries - 10% of these being the explosive type. Everything was shaping up well just before take off at 7:15 pm & all the kites were lined up raring to go. Old Sanders was off first in 424 in O for Oboe & then W/C Clyde Marshall in T Tare. The runway was pretty icy but it didn't seem to bother them much. I was up in the Control tower as per usual checking the kites as they took off. W/C Ted Williams who was to take over 424 Sqdn. from Marshall when he finished his tour was third off in S for Sugar. I watched his lights down the runway & thought he was safely airborne when for some unaccountable reason the lights didn't seem to lift as they should & the thought flashed through my mind Oh oh, here it comes! Sure enough it did! If it hadn't been so horrible it might have been very pretty. A great blinding flash of flame rose up followed by thick billowing clouds of black smoke right at the intersection of the two runways. At intervals of a second or so the pyrotechnics were going off in all colours of the rainbow & then the incendiaries started with their vivid white flames interspersed with the occasional explosive one which sent up streamers of white fire in all directions & silhouetted against the black clouds of smoke & reddened by the flames underneath. It looked very much like the Toronto Ex. fireworks especially with the sharp chattering of the machine gun ammunition going off in the background.'

'The crash trucks & ambulance raced out immediately while we endeavored to think out a way of getting the other 11 a/c away on the op which of course always comes first. Unfortunately the crash blocked off the only two cleared runways while the third hadn't been cleared of snow yet so we were stuck & cancelled the rest of the op for good.'

'When the crash occurred, it shook the building a little but not as much as if a big bomb had gone off so we decided that the 2000 pounder hadn't gone off yet. We knew from experience that it takes almost a half hour for a 2000 pounder to heat up enough to blow up in a fire so we had to work fast to prevent any more damage to the aircraft parked near the crash. W/C Tambling & I raced out in his car to see what we could do with 15 minutes of our half hour grace already gone. We picked up Squadron Leader Stinson on the way & decided to start up and taxi the two nearest kites away from the vicinity. I climbed in with Tambling first to get him started & noticed he was so excited he tried starting the engines without turning on the fuel cocks nor his booster mag switches. For some reason or other I hadn't got too excited yet & fixed him up ok. The minutes just seem to tear by before we got him started up & away he went. I hopped out then to get Stinson going - he hadn't even got his engines started yet & there was less than 5 minutes to go! I had to make up my mind whether to start running for safety or go to help him which of course didn't leave much choice. Exactly on the half hour mark we got two of the four engines going but to get out of the dispersal area we had to taxi up nearer the blazing wreckage than ever - about 50 feet or so between me & a 2000 pounder ready to go up at any second - more darn fun. Anyway, after what seemed ages & ages we made it out ok & got well away from the crash.'

'Back at the control tower crash truck had returned to say that there was one survivor - the tail gunner who was only slightly bruised but was quite dazed from shock & found wandering around on his feet amongst the debris. By the time an hour was up the fire almost out & still no bomb gone off, we ventured out to find a great crater about 20 feet deep & 40 feet across - it had gone off the moment of impact! All our taxiing a/c to safety was for nothing but still exciting enough when we didn't know what was going to happen. Blast always seems to work in peculiar ways & what seemed to us like a very small explosion from petrol tanks from the comparatively close vicinity of the control tower shook everything up as far away as Leeming & threw people out of bed a few miles away. The bodies were all recovered finally in pieces & so we packed up for the night to get some sleep. As a slight aftermath, when I got to my billet all the parcels & groceries which I had sitting on a shelf in my room had been blown off on to the floor including my nice birthday cake - candles & all which I hadn't eaten yet - the one Mrs. Mac sent me.'

'Note - I believe this was the event which earned the MBE for me, Jan 1/1946'

424/433 Squadrons, Skipton-on-Swale - February 1945 to May 1945

Crash of 433 Lancaster NG460 1945-02-01

LW164 with Flak Damage 1945-02-10 - Ross Dawson 4th from left

Easter Egg for Hitler - RF128, Ross in the middle

Servicing Wing Control Board

Ross's well-used Hillman van at Skipton

Lancaster bombers in action over Wangerooge, 25th April 1945 Source: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk Catalogue ref: AIR 14/3647

'We had seen the flames of a crash in the distance but didn't figure it was one of ours. Nevertheless, it was Stinson who piled in over near Dalton in a terrific smash up. Two of the crew bailed out in time but the other 5 bought it'

Ross investigated the crash the next day.'What a horrible mess it was. It looked like he was in a power dive when he went into the deck at about a 30 degree angle . . . Three of the four engines were buried in the mud out of sight with only the tip of one prop blade showing. The fourth engine had been torn out & was burst alongside.' Ross provides a gruesome description of the crash site and concludes 'The only explanation of why it piled in was from the story of the two crew members who bailed out - they were badly shot up with flak over the target & it is thought that his controls must have suddenly given way.'

Unfortunately, their first operation with Lancasters on February 1 was marred by the crash of 433 A - Able piloted by Squadron Leader Stinson.

Operations continued apace and on February 13 they had 14 aircraft on an overnight operation which 'looks like they are going over to help the Russians on their front this time with a 9 and a half hour trip - ETR not being until 0650 tomorrow morning - that should take them a round trip of nearly 2000 miles.' On February 14 he notes, 'Well, as I expected, the target last night was in direct support of the Russians - Dresden got a real pounding with a big follow-up attack by the Americans. Today we got 4 away on bombing from 424 - Chemnitz near Dresden was the target.' This massive bombing of Dresden on February 14 and 15, 1945, caused a fire-storm which killed more than 20,000 civilians, and was one of the most controversial bombing decisions of the war. One of the few times I recall my father ever mentioning his time during the war was decades later when he lamented his role in this horrible event on seeing an air photo of the devastation caused by the Dresden raid.

Gardening

The Crucible of War 1939-1945: The Official History of the Royal Canadian Air Force, Volume III

'The Group 6 airfields were well located for mining Baltic and Scandinavian sea corridors as there was considerable traffic to Norway, Sweden, and the Eastern Front. These so-called 'Gardening' operations were frequent missions for Group 6 bombers and over time a number of Group 6 squadrons became recognized as Gardening specialists. In early 1944 new mines became available. Following successful high-altitude trials undertaken by Group 6 squadrons, high-altitude deployment of mines became standard practice. . . . Early in the war, enemy defenders were able to easily identify Gardening forces as separate from a more major bomber stream because they approached the enemy coast at low altitude, and were not four-engine bombers. For this reason they played no role in deceiving German controllers as to the location of the main bomber stream. But a Gardening mission flown at 15,000 feet with four-engine aircraft could deceive the enemy as to the destination of the main bomber attack, and this strategy was used repeatedly throughout the remainder of the war.'

The next month was a period of intense bombing with operations to Dortmund, Mainz, Mannheim, Ruhr Valley, Cologne, Chennitz, Dessau, Essen, Zweibrucken, Dortmund (again) and Hagen along with regular gardening operations in the Kattegat. The operations typically were scheduled to depart early in the morning which meant Ross and his crews had to work overnight. While they continued to achieve excellent results on the mechanical side a number of aircraft and crews were lost on subsequent operations. These included a number of Ross's friends. On March 6: 'Unfortunately we lost Flight Lieutenant Don Ross in H of 424 - it sure is too bad since he was a swell guy & of course went through Riverdale Collegiate with me at home.' And on March 7 'We lost two shot down from 424 Sqdn - C with Flying Officer Foley as pilot & N with Flying Officer Lighthall as skipper.' On March 12 'Flying Officer Farrel in E 433 Sqdn didn't come back.' The operation on March 14 was to the Zweibrucken railway yards in support of the American 3rd and 7th Armies in their drive through the Saar basin. 'According to the boys it just doesn't exist anymore after tonight. We had 12 from 424 & 15 from 433 on with 10,660 lbs of HE's up on each - no failures or missing kites.'

March 25 was a very difficult operation as 'We had 14 kites badly shot up with flak after today's do including 4 3-engine landings. However there were none missing altho' I guess it was pretty tough on the boys & there were a lot of narrow escapes. We were digging flak pellets out from all over the place & L of 433 had a hole 12 inches in diameter in the petrol tank & we got the biggest single piece of flak I've ever seen yet out of it - a piece about 12 x 3 x quarter inch'. In his Operations Summary table for a March 31 operation to Hamburg he notes, ominously, 'First appearance (in force) of ME262 jet operated German fighters - faster than 500mph & armed with rockets and 30mm cannons. Shot down 5 Lancs & 3 Halifaxes in Grp 6.'

On Easter Sunday April 1, 1945, 424 Tiger Squadron operated its 2000th sortie of the war to Hamburg. The armorers celebrated the occasion by painting up a 4000 lb 'Easter Egg for Hitler'.

Ross finally began to have some real optimism about the war ending. In the next few quiet days at the aerodrome he wrote, 'The Armies are really going to town now & have broken through all the way to the Rhine for the whole length & even the Remagen bridgehead.' On March 28 they prepared for an operation, 'However it was scrubbed at the last minute & after no less than 3 bomb load and petrol changes - we later heard that General Patton's army captured the town we were supposed to have hit.' A very similar thing happened on April 3, with many changes to a planned operation which was finally scrubbed because 'Gen Patton's tanks arrived at the town we were to bomb too soon.' While the intensity of operations began to taper off, they were still a month away from their last sortie.

On April 5 'A/C Roach came to pay us his inspection visit - seemed quite pleased with the station & our work & looked over everything thoroughly. Also liked our new Servicing Wing Controller idea.'

While they did not know it at the time, 424 and 433 Squadron's last operation of the war came on April 25, when ten aircraft from each traveled to 'the little island of Wangerooge near Wilhelmshaven Bay. It was such a good attack, the boys say they nearly sank it! We had a little excitement getting them back on the deck again since it was quite foggy & they were bouncing all over the place. Also W/C Norris's kite O Oboe of 424 was badly shot up with flak & the Flight Engineer wounded in the thigh. The navigator had a very lucky escape since the F/Eng was just climbing past him when the flack hit & it stopped in the meaty part of his thigh instead of the small of the Nav's back.' This was the last major allied air attack on German territory during the war which involved 482 RAF and RCAF bombers.

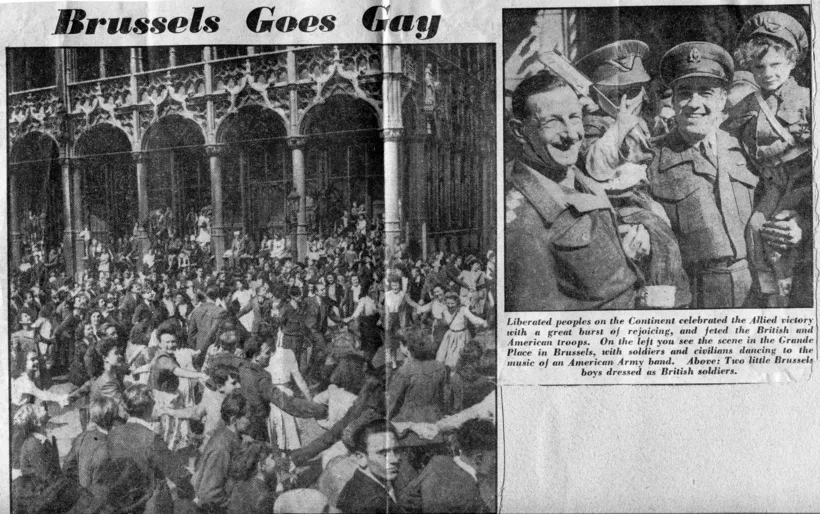

VE Day in Brussels - May 7 to 9 1945

On Monday May 7, 1945, Ross wrote, 'News came through this afternoon that the Germans were going to surrender unconditionally tomorrow & that Churchill & the King would be speaking tomorrow afternoon so it looks like the long-awaited day is here at last. Got back to the station tonight & found things in a panic with 13 kites needed from each squadron tomorrow to go over to B58 aerodrome near Brussels to pick up 24 released POWs in each kite & bring them back here. We had to arrange Mae Wests for them all, paper sick bags, cushions and rations. Moreover, found out that there was a servicing kite to go over too; complete with ground crew, tools, equipment & most important of all - an engineering officer! - boy I'm in here like a duck!' He pulled rank and assigned himself the task of being the engineering officer on the operation.

The following day, May 8, he wrote, 'We got airborne at 10:30am . . . The day was very warm & bright & I enjoyed the trip from the nose of the aircraft in the bomb aimers position where I could see all there was to see. . . we passed over close to Antwerp, circled Brussels and finally found our aerodrome B58 at a little town called Melsbroek . . .. This aerodrome was one of the ones camouflaged by the Jerry to look like a village. The flying control building looked like a school house complete with tower and bell. The area was laid out in streets with what resembled houses & stores along both sides. However, on closer inspection the buildings were all shells housing hangers, workshops, garages and billets etc. The fronts were of wood & all painted to represent windows, doors, signs etc. but actually were big doors which opened out when in use. It sure looked like a lot of work for what they got out of it. We also saw a building which had a big sign POW lettered on top of it but which actually held petrol and oil stores . . .'

'We finally reached our parking strip & got out to be confronted with approx.. . 3000 POWs of all nationalities, types & colour dressed in every sort of cast-off clothing imaginable with khaki being predominant of course. We had to wait about an hour for the first of our kites to come in so we talked to a group of them. There were Aussies & New Zealanders, Canadians & Americans, English & Poles & Russians etc. of army, navy & Air Force. Several Canadians came up to speak to us having recognized our a/c letters. Even some from our own Sqdn . . . They didn't look to be in too bad condition but their camp (Stalag 3) I guess was one of the better types. However, they were all half starved & for every one of them who could move they said there were 3 left behind who were too weak to move or were in hospital etc.'

'As soon as our a/c started to land the work really started & we spent all afternoon rushing up and down the long line of 75 to 100 planes getting them loaded with 24 POWs each, fixing snags and getting them off again. As soon as one kite moved out of line another would land & take its place so it really was quite a major effort. It was hot a grueling work & I sure began to get tired.

'There was no place to eat or drink except a NAAFI canteen with a queue about a mile long for which we didn't have time to wait, so about 2:45 Flight Sergeant McIntyre & I seeing this little village off to the side of the aerodrome decided to walk out and see what we could find. We had no Belgium money but I had a spare pack of cigarettes which I thought I might trade for something. We hadn't gone far along this little cobblestone street in Melsbroek until we came to what looked like a pub with a horse & wagon parked outside. The wagon was piled high with cases of wine etc. & we decided that this place looked interesting & wandered into a little covered courtyard along side. Here was a typical Belgium woman complete with big wooden sabots washing down the cobblestone court. She couldn't speak English so I started off half-heartedly in my very weak French & not knowing quite what to say. However, she seemed to understand very well & took us each by the arm & conducted us into their kitchen where her husband & two other men & a boy were seated around the radio listening to Churchill speak at 3:00 o'clock - it was being re-translated for them as he went along. They all greeted us happily with big smiles, violent arm waves & much jabbering out of which the expression 'la guerre est finie' came out very frequently. The lady bustled around & got us a glass of beer apiece - stuff called Kirstch Biere & tasting faintly of cider. It turned out that the boy could speak a little English so he acted as interpreter for us & we got along quite well. Next out came the Cognac & we had two glasses of that & then the old boy got out a box of cigars & handed them around so we were quite happy. . . .'

'We said goodbye & left shortly after & went back to the aerodrome to get cracking again. About 4 o'clock one of our aircraft 424 Q burst a tyre on the runway just before takeoff. . . .we took all the stuff out to the kite, started to jack it up & were making good time - figuring it would be done by 8:30. However the wheel was in soft earth off the runway & we had just removed the old wheel but hadn't put the new one on when the jack started to sink in the soft earth . .. There was nothing else we could do until we got some more jacks so I went to Flying Control to arrange for more jacks & to get red lights put around the kite then we headed for Brussels.i

'We . . . thumbed a ride on an RAF truck which deposited us near the famous Botanical Gardens in the centre of Brussels. Flight Sergeant McIntyre & I then headed for an hotel whose address had been given us before we left & arranged for a room. Then we started out to see the sights. By this time, it was about 10pm & there was lots to see. First of all, there were terrific crowds of people milling & weaving around all the streets & squares celebrating VE Day 'La guerre est finie' was the popular cry & many tears of rejoicing were seen too. Long snake dances were formed of soldiers & girls tearing around, huge American trucks were loaded to capacity with people perched all over the place on them careening wildly up & down the streets. Everyone was shouting & singing, throwing streamers & confetti, girls would rush up and kiss us & then tear on again - what a wild place it was! The next big thing I noticed were that all the lights, neon signs & flickering advertisements were on full blast - the first lights I've seen like that in 2 and a half years & it sure did make me a little homesick for the moment. About every other shop seemed to be a cabaret with a band playing, sweating dancers crowded inside & cool-looking drinkers sipping their Champagne & Cognac out on the sidewalk fronts separated from each other by canvas marquees. We started visiting the cabarets one after another & trying all new drinks until it appeared that our money would run low so we stuck to beer after that - very poor stuff actually more liked coloured water. There were innumerable occurrences and happenings during the evening but all-in-all we spent a very gay & happy time arriving back at our hotel around 2:30am tired out and very much in need of sleep. We tumbled right into bed & so to sleep with the sound of revelry still going on strongly till well after 6:00 am. . . .'

VE Day - Ross Dawson with Champagne

'Wed May 9: Got up about 8:00 pm & set out to find our way back to the aerodrome. Some revelers were still going strong when we got out. After trying my French out several times we finally caught a train & got back out about 10:00 am. By dint of great exertions & the use of two mosquito jacks we finally got the wheel changed & taxied it out of the mud in time for lunch at 1:30 - only my second meal since I got over here. I went up to the Officer's Mess & really filled up. Bought a bottle of Champagne for 140 francs & we got airborne at about 3:30pm. I slept most of the way back & we arrived here about 6:00 o'clock in time to tell all our stories to the boys around the bar for the rest of the evening. It turned out that 11 of each Sqdn were away today picking up more P.O.Ws at Juvincourt France (near Rheims) but no servicing party required this time.'

Home

Even after a big VE Day celebration life goes on. 'Thur. May 10: VE Day or not, we still seem to be very busy with 15 a/c from each Sqdn away today to Juvincourt for more P.O.Ws. It is very hard on the kites landing them over there with their bad runways & cutting tyres etc. we had to work all night tonight in preparation for tomorrow.' But they then had a few days with no ops and the reality began to sink in.'Finally the war is over! It sure is a wonderful feeling.' There were dinners and parties in the evenings. On Sunday, May 13 he 'slept all afternoon, went to the show tonight & then had a big feast of canned corn, sausages, eggs, peaches, toast & lots of chocolate before going to bed.' Presumably he felt no need to continue hoard the comfort food he had received in parcels from home. And on May 16, 'down to the local pub tonight for a few beers & dart games. Came back and fried two eggs before going to bed - it is a great life but very boring.'

On Friday, May 25, there was a 'Sudden panic today with Far East Declaration forms to fill out for everybody & get in to HQ by June 1st. . . .I volunteered for the Far East - maybe I'm crazy but I have a feeling that it is the best thing to do.' It is unclear whether volunteering made a difference to when he was able to head home, but later that day his boss, the Chief Technical Officer for Group 6 found him. 'Tiny Smith from Group HQ came in & out of the blue sky asked me if I wanted to go home. Of course I said sure & he said OK pack up - you are posted to Croft & will be home by the end of June. That was all there was to it, so I immediately started getting clearances signed.

Ross was assigned to two squadrons heading back home, 431 and 434, with Lancaster X's. The aircraft were to fly home the following week, packed up with spares & parts. Ross would stay with the 'main party . . and set everything right on the station,' before leaving by ship two weeks later.

On Tuesday, June 12, he 'found out I've been put in charge of the second train leaving at 0355 hrs tomorrow morning. . . . Got my 200 odd men sorted out complete with luggage & loaded them on trucks at 2:00 am. Everything went smoothly & the train pulled away sharp on time. . . Some of the boys had apparently swiped some Very pistols & lots of cartridges since they were shooting them off in all colours all the way up to Edinburgh. I was a little worried about starting fires in farmer's haystack's & on roofs etc. but couldn't do much about it since I couldn't get up to their part of the train with a baggage car in between. . . We all had a whale of a time leaning out the windows & hollering at everyone & waving etc. as we passed through cities, towns and villages. They all knew who we were of course & gave us a great welcome. At about 12:20 we arrived at Gourock -the very port where I arrived at 2 yrs & 4 months ago today.'

Ross came home on the Isle de France arriving in Halifax on June 20 and then by train to Toronto. On June 23, 1945, Ross, a veteran at 26 years old, 'Got into Union Station at 9:30am & waited patiently for 20 min & then on to the Exhibition Grounds. Here we piled out, formed into lines & got the old band playing & thence marched into the Coliseum with all the friends & relatives cheering & waving. It was quite thrilling but I didn't see anyone I knew until Kay & Trudy came bursting on me followed by Grandma, Nona & Stewart, Lenore, Dorothy, Bob, Bruce & Jean Merrill. What a reunion that was!'

Epilogue

Ross Dawson at the abandoned Skipton-on-Swale Aerdrome 1968

Thankfully, with the Japanese surrender on August 15, 1945, Ross was released from his commitment to fight in the Pacific. He met and married his true love, Eileen Willis in 1946 and they were happily married for 52 years until Ross's death in 1998. Ross and Eileen have three sons and four grandchildren. Following the war Ross worked for 15 years with the Ford Motor Company in Oakville Ontario in facilities planning. He then became one of the first employees of York University in Toronto. When the campus was still a farmer's field in 1961, he joined the Campus Planning Department and eventually became the Director of Campus Planning.

Ross was a quiet, gentle and kind man who was exceptionally competent, and had a strong personal code. He very rarely mentioned anything about the war and his experiences to the family. He never wore his uniform or medals, or participated in any active way in Remembrance Day ceremonies or other military events or social gatherings. The friends he stayed in contact with were all people he knew from before the war, none of his war-time acquaintances. His extreme reluctance to talk of his wartime experiences in later life stands in stark contrast to the detailed personal records he made during the war, and kept in a trunk in the basement for the following 50 years. In hindsight, I believe Ross never fully came to terms with the horror and brutality of his war experiences, the moral and ethical issues related to the war, and his role in it.

Bill Dawson, June 2021