Flight Lieutenant David Hornell VC Story

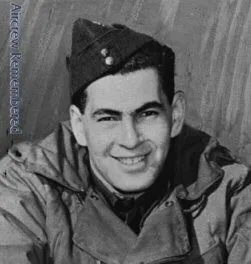

Ottawa Journal 1944-07-28. Enhanced and colourized by MyHeritage.com

David Hornell, VC

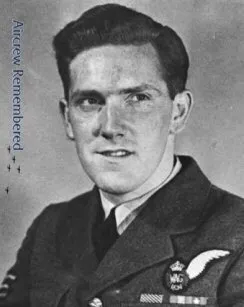

A younger David Ernest Hornell

Early Life

David Ernest Hornell hadn't needed to volunteer. Born in Toronto, he'd lived almost his entire life in Mimico, moving there with his family in early childhood after his mother died. His father, who operated a women's apparel firm called the Hornell Fashion Waist Company, eventually remarried and Hornell grew up in a duplex shared with an aunt and uncle.

"Bud""as he was nicknamed by his younger sister Emily, whose attempts to say "brother" sounded like "buddy""attended John English Public School and Mimico High School. A bright student, he graduated with honours and proved to be an avid enthusiast of rugby, tennis, swimming, and track and field.

Although he was offered a university scholarship, it was at the height of the Depression and Hornell opted instead for steady employment, accepting a job in the chemical department at the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company in nearby New Toronto. After his father's death in 1935, he also assumed the presidency of the family business, but appears to have left day-to-day management to his uncle. Some observers felt he'd limited his opportunities for career advancement as a result of the considerable time he dedicated to church work. A long-time, active member of the Wesley Mimico United Church, Hornell was a teacher and superintendent of the Sunday school.

A friend, the Rev. A.E. Black of Wesley Mimico United Church, characterized Hornell as "a good Christian, one of the finest men I have ever met. He was refined, cultured, fond of poetry, and artistic, possessing a most unselfish disposition." For well over a decade after graduation, the fair-haired and mustachioed young man seemed settled into a comfortable, if mundane, life.

Had he not volunteered for uniformed service, David Hornell would certainly have secured a deferral on the grounds of his age (he was over 30) and his employment in an essential wartime industry. Then, on January 8, 1941, seemingly on the spur of the moment, Hornell enlisted with the Royal Canadian Air Force"a decision he later admitted was hasty.

Hornell "wasn't in flying for the love of adventure," a Globe and Mail (July 29, 1944) profile later explained. "He was doing a job because there was a war. He had no thought of staying in flying when the war ended." Although Hornell's precise motives are unknown, perhaps a sense of familial obligation loomed large at the time of his enlistment. His cousin Alan"Ash's younger brother"was suffering with pneumonia at the time (and would die within the month), and his own younger half-brother, William, soon followed him into the RCAF, serving as a bombardier-navigator in a Halifax bomber over northern Europe.

Genevieve Madge (Noecker) Hornell, married January 1943 while on leave in Mimico Ontario. Honeymoon at RCAF Station Coal Harbour Vancouver Island. Newspapers.com

RCAF - Training

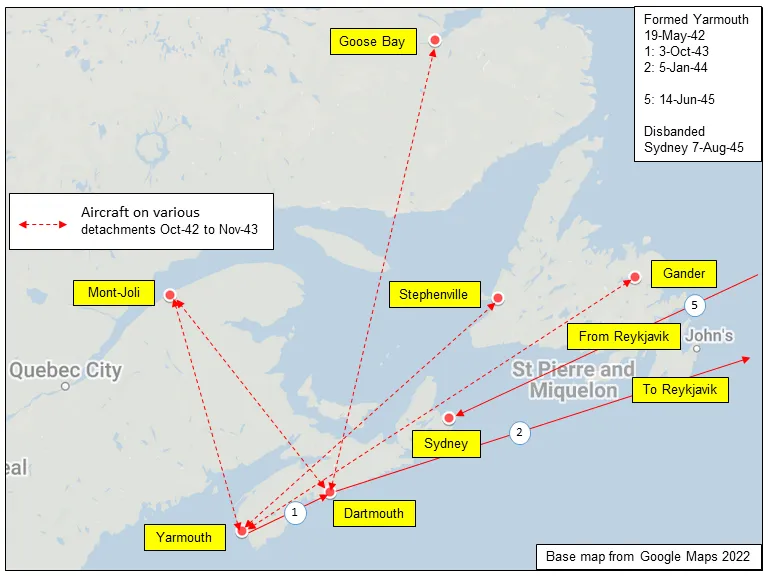

Hornell received his initial pilot training at the Brantford Service Flying Training School that summer, and did a further course at Charlottetown to qualify as a navigator. Just before Christmas, he was assigned to the 120 Squadron RCAF, flying coastal patrols from RCAF Coal Harbour on the northern tip of Vancouver Island, and occasionally acted as a test pilot for the Canso flying boats being produced at Boeing's Canadian factory in Vancouver.

RCAF - Coastal Patrols British Columbia

The coastal patrols could be monotonous, since few enemy vessels ventured close to Canadian waters on the west coast. Nevertheless, Hornell earned the respect of his colleagues. "Flying Officer Hornell's work has been consistently thorough," a superior once noted. "A very mature and well balanced type of officer."

He was joined in Coal Harbour by his new bride: a tall, blue-eyed music teacher named Genevieve Noecker, after their marriage in Toronto on January 26, 1943. A few months later, he was promoted to Flight Lieutenant. "At this point, David felt he'd never be posted overseas "It was generally accepted that the air war in Europe and the South Pacific was a war for very young men. David and his bride settled down to a fairly routine life at Coal Harbour."

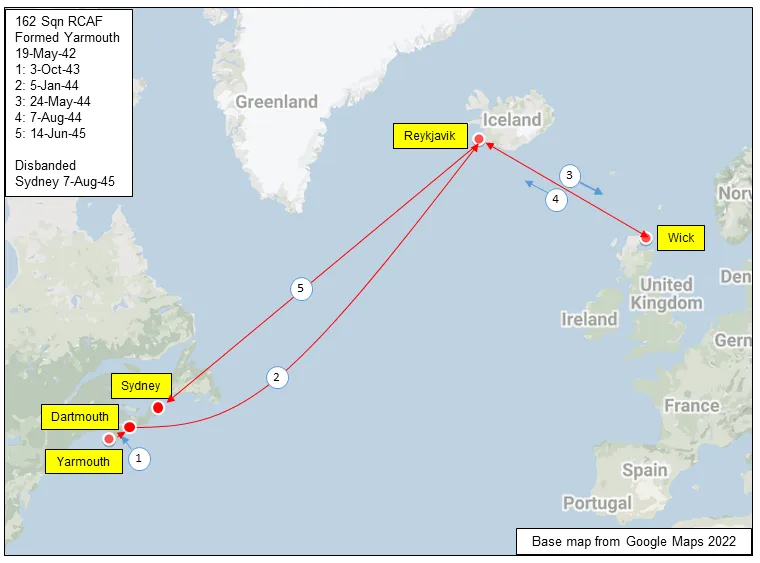

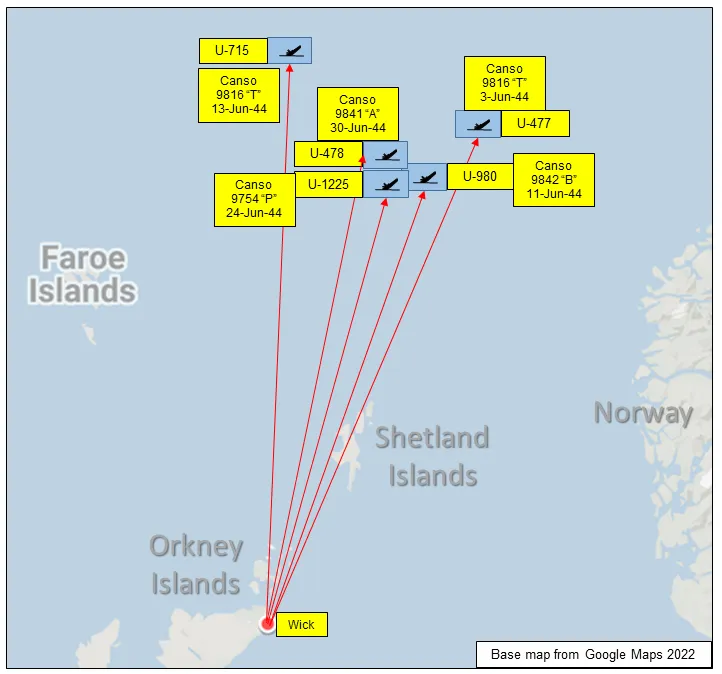

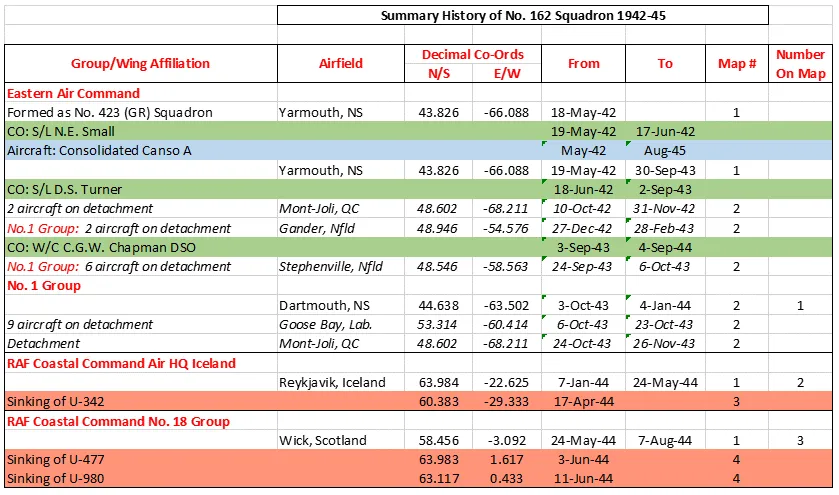

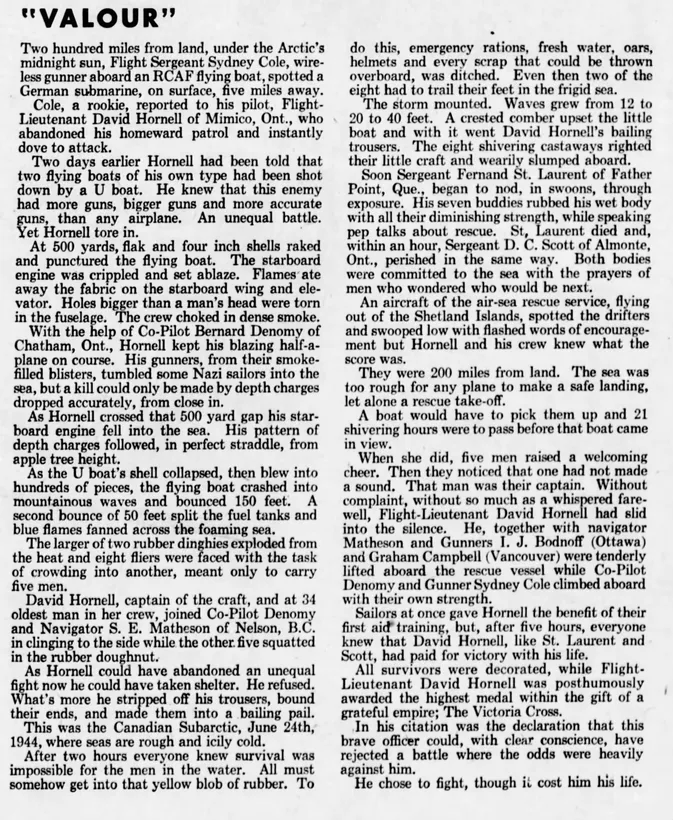

RCAF - 162 Squadron

In late September 1943, as a capable pilot experienced in coastal patrol operations, Hornell was transferred to 162 Squadron RCAF, operating Canso A aircraft on the Atlantic Coast.

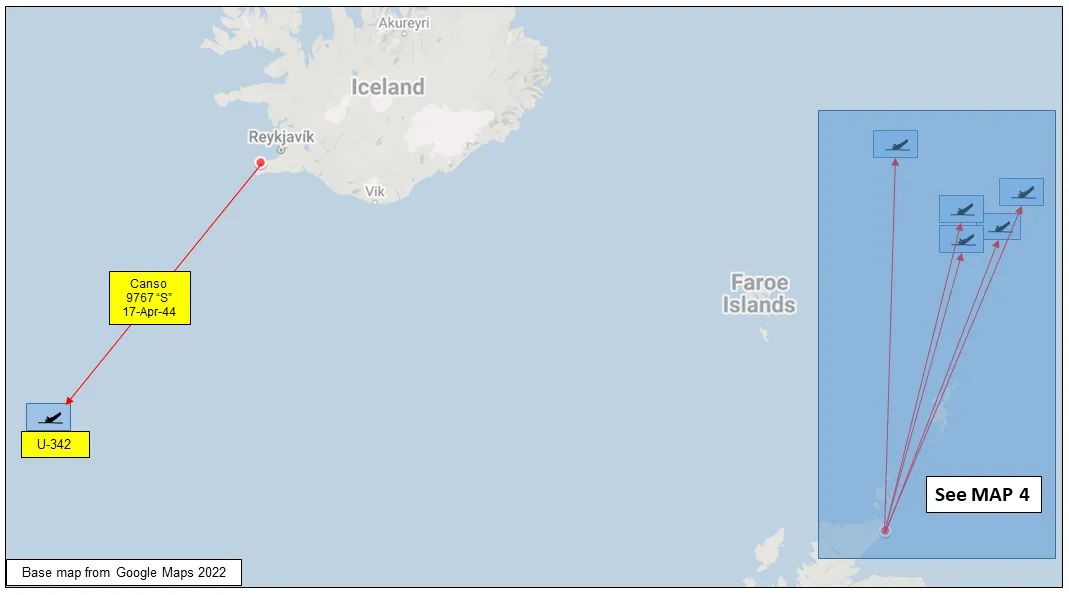

By the new year, the squadron"and Hornell"was deployed to Reykjavik to provide mid-ocean air cover for North Atlantic shipping routes, where convoys were most vulnerable to German U-boat attack. The Canso (the Canadian-built version of the Consolidated PBY Catalina) was a painfully-slow, long-range twin-engine amphibian plane with the ability to land on and take off from water and a standard airstrip. Capable of being armed with an assortment of bombs, torpedoes, and depth charges, along with .303 Browning machine guns in the nose turret and in the two side fuselage blisters, the Canso was tasked with locating and engaging enemy submarines stalking the North Atlantic.

Location of Sinking of U1225 as taken from Uboat.net

Later that spring, Hornell's was among the small number of Canso flight crews temporarily assigned to operate out of Wick in northern Scotland. His flight crew at the time included co-pilot Flight Officer Bernard "Denny" Denomy from Chatham; navigator Flight Officer S.F. "Edward" Matheson of Nelson, B.C.; wireless air gunner Flight Officer Graham Campbell of Vancouver; gunners Sergeant Joe Bodnoff of Ottawa and Sergeant Sydney Cole of Long Branch; and engineers Sergeant Donald Scott from Almonte and Sergeant Fernand St. Laurent of Pointe-au-Père, Quebec. Most were much younger than Hornell and nicknamed him "Pop," but looked up to him as a natural leader.

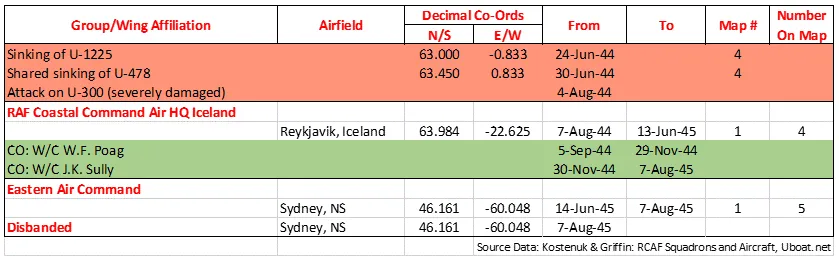

Engagement with U-1225

On June 24, 1944, 162 Squadron had six Canso A aircraft on operations out of Wick, Scotland and two more in transit from Wick to Reykjavik, Iceland. This was Hornell's 60th operational mission and was proving to be entirely uneventful. After 10 hours of routine patrol with a clear horizon on all sides, the crew was fighting boredom and fatigue as they neared the end of their day's work. At 19:00, 400 kilometers north of the Shetland Islands somewhere between Iceland and Norway, Bodnoff spotted a surfaced submarine (the U-1225) about five miles off the port beam, travelling at high speed. "Do you see that sub, Dave?" Bodnoff asked the captain over the intercom. "I sure do," Hornell replied without hesitation as he turned the plane to attack. Still four miles off, the submarine opened fire from its deck guns"an indication that her captain wasn't intending to dive but to fight. Flak exploded all around the slow-moving plane, causing it to shudder and vibrate violently. "The whole side of the ship popped full of shrapnel holes till it looked like the top of a salt shaker," recalled Cole, who was manning the radio. A native of Northern Ireland who'd grown up in Long Branch and briefly worked at Goodyear's New Toronto plant, Cole joined the RCAF in 1942 and had arrived overseas just a few weeks earlier.

"I pulled my knees up to my chin, tucked my head between my knees, to make as little target as possible and started sending S.O.S.'s [sic] for all I was worth," Cole recalled of the scene as flak exploded on all sides of the fuselage. Although he didn't immediately realize it, the Canso's radio equipment was damaged in the firefight, and none of his messages were received at Wick.

The submarine's anti-aircraft proved fierce and accurate. The starboard engine was struck and burst into flames. "All the fabric was off the starboard wing, with only the bare ribs showing," Cole said the damage. "The fabric on the starboard elevator was gone and the leading and trailing edges of the wing were blazing furiously. The cables were damaged."

Undaunted, and with the help of his co-pilot, Hornell pressed the attack, struggling mightily to control the crippled plane. When the Canso closed within the 1,200-yard range of its .303 Brownings, the gunners returned fire, spraying the submarine's conning tower with rounds. Denomy detailed the series of events from his own vantage point:

Bud guided the badly damaged aircraft into the attack. Before long our starboard engine, which was burning, broke loose from the wing and fell into the sea. Bud fought with the controls which were damaged, either from the anti-aircraft shells or from fire, we did not know. With one engine gone and the aircraft afire we had a tough time trying to keep the aircraft trimmed and at the same time press home the attack. This, however, he did and we coasted in to within thirty or forty feet above the enemy sub and loosed our depth charges.

The depth charges straddled the target perfectly, and the resulting explosions heaved the U-boat out of water before it crashed back down in a cloud of spray.

Setting Down Canso 9754 in the Sea

With no time spare cheering the sinking of the U-boat, Hornell struggled desperately at the controls to gain altitude"back up to 250 feet"and edge the aircraft into the prevailing wind. With a single engine and flames streaming from the fuselage and wing, there seemed little hope to ditch the Canso safely in choppy seas. But Hornell managed it, skipping 150 feet off a 12-foot wave, then bouncing another 50 feet before hitting the ocean again.

"We set her down surprisingly easy," Denomy recalled understatedly, "but we got out in a hurry because we were afraid she would blow up, she had been on fire so long. The cabin was full of nauseating smoke, so we couldn't stay in it for long anyway." Hornell and Denomy escaped through hatches above the cockpit; the others got out through the port blister. With water already at his knees and pouring in rapidly, Cole fumbled through the smoke-choked cabin to grab a cylinder of water and a can of emergency rations"but wasn't able to grab the emergency radio"before escaping. In less than 10 minutes, the plane would be out of sight beneath the waves.

Other crew members had grabbed the plane's two inflatable dinghies, though an equipment malfunction made one of them unusable, and isolated St. Laurent in the water at some distance from the rest of the group. Removing his flight pants to make it easier to kick, Hornell swam over to retrieve the flight engineer, and return to the lone remaining life lifeboat.

Worried about over-burdening the five-man craft, Hornell, Denomy, and Matheson remained in the seven-degrees-Celsius water, immersed up to their necks and clinging to the side of the dinghy. For the next few hours, the eight survivors took turns in shifts, alternating between being aboard the vessel and submerged in the frigid North Atlantic, kicking their legs constantly to maintain feeling in their limbs, and heaving their shoulders and chests out of the water every of often to gain whatever warmth they could from the long hours of summer sunlight that far north. After each fellow's turn in the water, the others would rub his limbs to restore circulation. Feeling a sense of obligation to his crew-mates, Hornell spent more than his share of time in the water.

Although the air force predicted airmen could survive up to 24 hours in a dinghy, Cole later informed the press, "from the chill in our own bones we knew we couldn't live even that long if we had to spend part of the time in the icy water." So it was decided to squeeze everyone aboard the lifeboat, with some dangling their legs or arms over the side. To make room, all non-essentials"including the emergency rations and fresh water"were tossed overboard, since the airmen rightly figured that death by exposure would come far sooner than starvation.

With the lifeboat already lying low in the water, the crew bailed water constantly. Denomy handled most of the work with his flight helmet, and the others did what they could using Hornell's trousers tied tightly at the legs as a bucket.

As the night wore on, the dinghy was tossed helplessly on increasingly violent waves"rising to 20, then 50 feet"as winds swelled to 60 knots that night. "We had to lean over to counter-balance the boat when taking the bigger waves," Cole recalled of their efforts to keep upright, "and we were all pretty stupid and groggy, and were right on the crest, and flipped us over neat as a pancake." The dinghy capsized like this at least twice, though they managed to right it and clamber back aboard. The crew huddled together as protection from the cold, taking particular care to keep Hornell, who'd sacrificed his pants to the bailing efforts, shielded from the wind. For his part, Hornell remained cheerful and kept their spirits high.

Occasionally, debris from their U-boat kill drifted by, including the body of a German sailor floating face down. "We didn't know if he was live or dead and didn't much care," Cole later stated matter-of-factly. "We didn't have room in our dinghy for enemy survivors and I grabbed a can of water to bash him over the head if he had tried to come aboard."

After five hours adrift, under the midnight sun, a Catalina flying boat operating from Scotland with a Norwegian crew sighted flares shot off by Hornell and his crew. Although seas were far too rough for the plane to attempt a landing, the Catalina used a signal lamp to flash a message: "Courage"H.S.L. [High Speed Launch] on way"help coming." A second message confirmed the sinking of the U-boat, which prompted a cheer among Hornell's crew aboard the lifeboat.

The Norwegian plane circled for 14 hours, keeping the survivors visible through the storm. A Warwick plane, arriving on the scene some 16 hours after the crash landing, tried to drop a second lifeboat by parachute, but wind and wave carried it far beyond the reach of the survivors. Hornell, who swam competitively in his youth, wanted to try swimming for the dinghy. But, perhaps knowing that even excellent swimmers lose their abilities in the harsh cold, Hornell's compatriots smartly restrained him.

In the U-boat attack and crash landing, the Canso's crew had suffered only minor injuries. But after 12 hours at sea, the weakened crew started succumbing to the effects of exposure. St. Laurent, the engineer, was the first to go. Although they tried to resuscitate him for a while, the survivors put him overboard. "There was no ceremony, but it was just as reverent and heartfelt a funeral as any held on dry land," Cole told the press. "We couldn't stand and we couldn't move in our positions, as we consigned him to the sea. I heard Denomy saying a prayer aloud, and I said one to myself, and I know all the other fellows did." An hour later, the other flight engineer, Scott, died and was likewise buried at sea.

He got his name "Bud" from his Sunday school students and, like his air-crew, they thought a lot of him. His religious training remained with him and almost his last words before he lost consciousness were a prayer.

Flight Sergeant SR Cole, one of the air gunners on the Canso, described the fliers last conscious moments:

"shortly after we were sighted Bud led us in short prayer of thanksgiving because we knew it was little short of a miracle that had caused an aircraft to happen along at just the right time." Ottawa Citizen 1944-07-28

The survivors' condition continued to deteriorate. Hornell couldn't see by this point, but still made efforts to comfort his crewmen, strengthening their resolve to survive and their determination that rescue would indeed arrive. On occasion, the former Sunday school teacher, led them in prayer.

By the time the crew, exhausted and near death, spotted a Sunderland flying boat leading an Air Sea Rescue Service launch towards them on June 25, they had been adrift in the North Atlantic for nearly 21 hours. "I let out a whoop, and everybody answered me but Hornell," Cole stated. "We realized then that he had become unconscious. We all said a bit of a prayer to ourselves as the rescue launch approached." The rescuers hoisted the survivors aboard, and worked furiously to revive Hornell from his terribly weakened state. He never regained consciousness, and was pronounced dead not long after being pulled aboard. With just minor injuries and swelling, the others recovered sufficiently in hospital. Hornell was buried on a hillside in Lerwick, Scotland.

On July 26, 1944, Hornell's widow Genevieve learned by telegraph that her husband was to be posthumously awarded the Empire's highest military honour, the Victoria Cross. Hornell would be one of only three RCAF members"and three Torontonians"to receive the Victoria Cross during the Second World War. "By pressing home a skilful and successful attack against fierce opposition, with his aircraft in a precarious condition," the official citation read, "and by fortifying and encouraging his comrades in the subsequent ordeal, this officer displayed valour and devotion to duty of the highest order."

A few days later, after the formal announcement of Hornell's Victoria Cross was made on July 28 by "Chubby" Power, Minister of Defence for Air, the news was splashed on the front pages of newspapers across the country. Genevieve was inundated with letters of sympathy and congratulations from the likes of Prime Minister Mackenzie King and Air Marshal Robert Leckie. Newspaper reporters scrambled to have Cole, Denomy, and the other survivors of Hornell's crew recount their ordeal.

Hornell's widow received her husband's Victoria Cross from the Governor General in a ceremony at Rideau Hall on December 12, 1944"the first time the honour had been presented in Canada. It wasn't until 1956, when all Victoria Cross recipients or their next-of-kin were invited to a reunion in London, that Hornell's by-then remarried widow was able to pay her respects at the airman's grave in Lerwick.

"If ever a fellow deserved the V.C. it was Flt-Lieut. David Hornell," Cole told the Star(July 28, 1944), speaking glowingly of the pilot. "The way he drove that one-engined flaming half-a-plane straight into flak almost too terrific for imagination, levelled her off right over the U-boat as coolly as if he was on a practice run, and dropped his depth charges for a perfect kill, brings a lump to my throat whenever I think of it." Like the rest of the survivors, Cole was also decorated for his part in the submarine attack and cold-water ordeal. He and his fellow gunner, Bodnoff, were awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal; the navigator, Matheson, and wireless air gunner, Campbell, each received the Distinguished Flying Cross; and Hornell's co-pilot, Denomy, was awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

Many Honours

There were numerous commemorations in Hornell's honour in the months and years following his death. A huge crowd, along with dignitaries like Air Commodore G.E. Wait, commandant of the RCAF's War Staff College, attended a memorial service for Hornell at Mimico High School on September 17, 1944. In early 1945, the last Canso flying boat built by Boeing in Vancouver"for the Australian Air Force"was christened the David Hornell. That June, his widow unveiled a portrait to hang on the walls of the York County Council building. The David Hornell Memorial Hall was built by the Royal Canadian Legion, and opened at Drummond Street and Royal York Road in November 1949 (but would be completely destroyed by fire in January 1951). David Hornell Junior School still stands on Victoria Street in eastern Mimico"and is also the site of a historical plaque.

Canso 9754 - Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum

At Hamilton's Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum, a Canso aircraft painted with the No. 162 Squadron markings is dedicated to the Mimico airman. Finally, most recently, one of the ferries serving Billy Bishop Airport has been named in the Victoria Cross recipient's honour.

Final toll:

- Flight Sergeant David Stewart Scott MiD - Killed in Action

- Sergeant Fernand St Laurent MID - Killed in Action

- Flying Officer B Denomy DSO - Survived

- Flying Officer G Campbell DFC - Survived

- Flying Officer S Matheson DFC - Survived

- Flight Sergeant S Cole DFM - Survived

- Flight Sergeant I Bodnoff DFM - Survived

Compiled by Malcolm Ramsay

From Winnipeg Tribune 1944-10-30 (Newspapers.com)

![]() 162 Squadron Catalina 9754 'P' Fl/Lt. Hornell, RAF Wick, U-1225

162 Squadron Catalina 9754 'P' Fl/Lt. Hornell, RAF Wick, U-1225

P

P