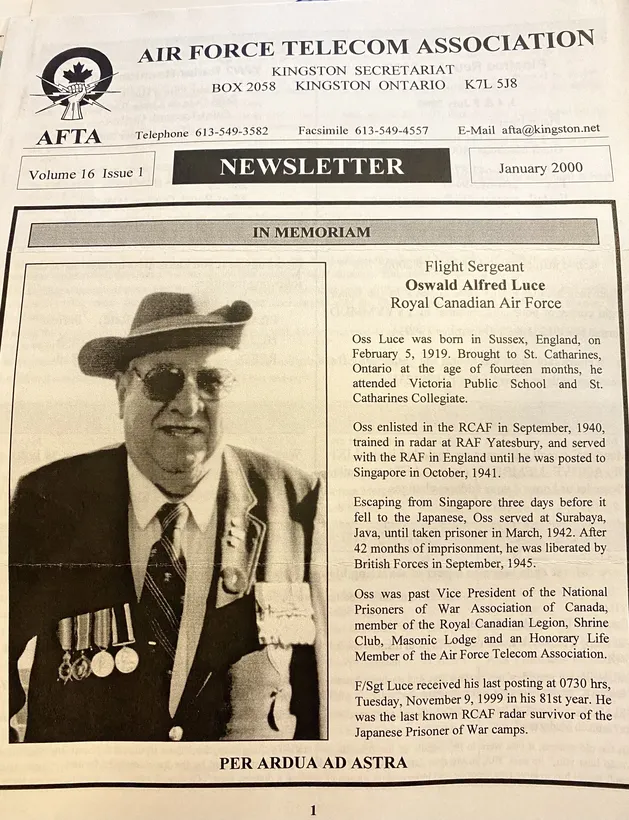

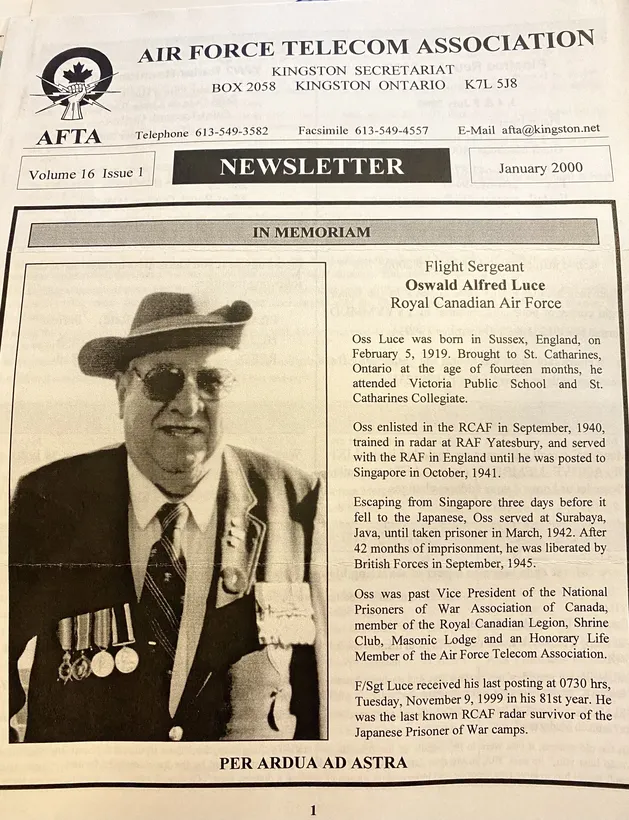

Birth Date: 1919-February-05

Born:

Parents:

Spouse:

Home: St Catharines, Ontario Canada

Enlistment:

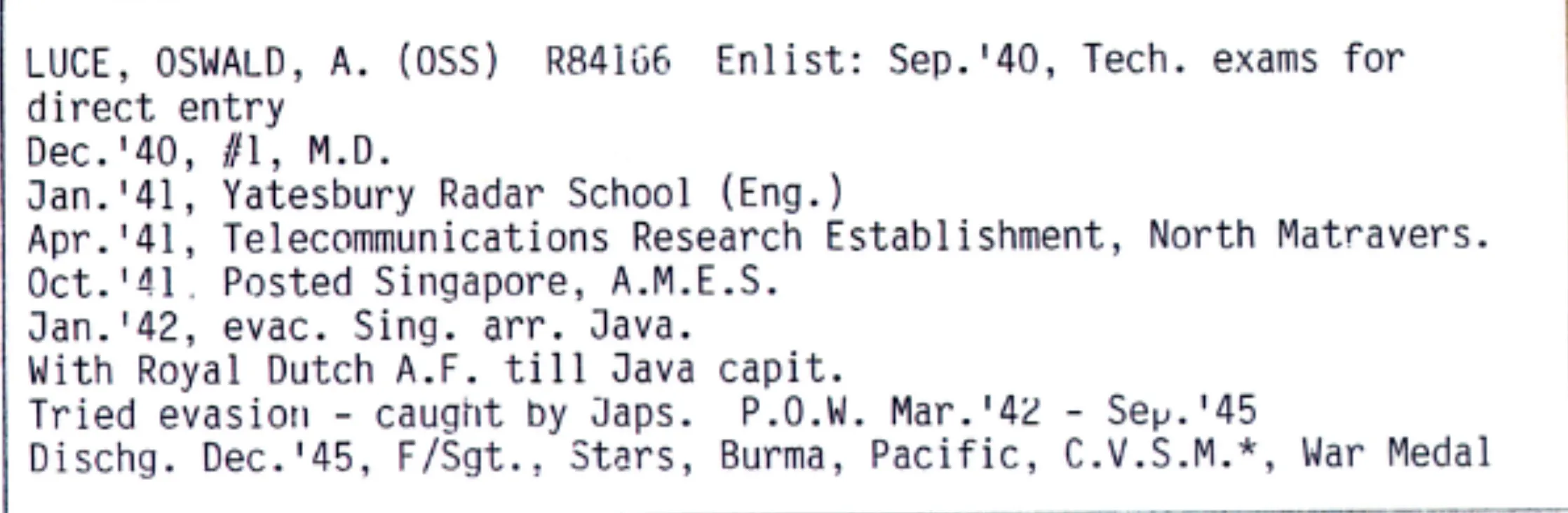

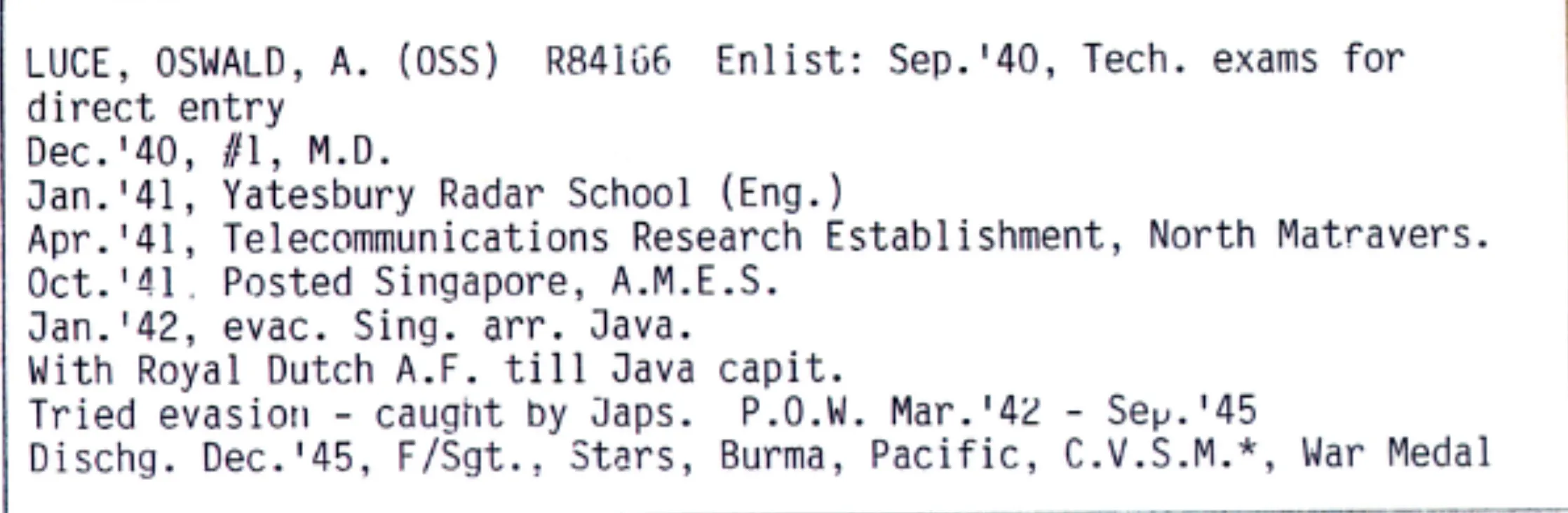

Enlistment Date: 1940-September-01

Service

RCAF

Unit

Base

Rank

Flight Sergeant

Position

radio operator

Service Numbers

R/84166

Experiences as a Prisoner-of-War, 1942-1945

Interviewed by

Charles G. Roland, M.D.

13 November 1985

Oral History Archives

Hannah Chair for the History of Medicine

McMaster University

Hamilton, Ontario

L8N 3Z5

Charles G. Roland, MD:

Mr. Luce, would you start by just telling me a bit about your background? A little bit about who your parents were and what they did and how you came to Canada, given that I know you were born in England.

Oswald Alfred Luce:

All right. My father had been in the navy, Royal Navy, for approximately 20 years. He and my mother were married during World War I. I was born in 1919. I have a sister a little older. They came to Canada in 1920, so my memories of England are nil. I went to school in Canada. What should I say? - my hobbies at that time were more electrical and mechanical. I studied, I used to do a lot of radio, amateur radio and so forth. Of course, I don't know if there's anything more. This led up when World War 2 started, about being asked, "Would I like to go to England, in civilian clothes?"

Roland:

Excuse me, what were you doing at that time?

Luce:

Oh, at that time I was working in a machine shop. I was a machinist in St. Catharines, an apprentice. They asked me if I cared to take a trip to England. Of course, everybody wanted to get in the war in those days. It was, oh, very early 1940. So to do that we had to take examinations in Hamilton, Department of Transport, I believe it was in those days, that would give us examinations on radio and so forth. Once we passed that we had to take our medicals and, if everything was suitable, we were then sworn in.

Roland:

How did you come to be picked out, you personally, do you

know?

Luce:

Yes, because I was in radio, amateur radio, and so forth, you see. And then, of course, the government knew that we had a background of radio.

Roland:

Oh, because you had a radio license.

Luce:

Yes, right, I had a background of radio.

Roland:

Fine. That's what I couldn't figure out, how they came to you, in a little shop in St. Catharines, and said, "Do you want to "

Luce:

Yes. That was the idea of that. Of course, at that time my mother was worried about warfare, living through World War 1, and so I made the promise I wouldn't go till after Christmas. I went to Hamilton, was sworn in, and I think we were on a boat in Halifax, somewhere around early February of 1941.

Roland:

What service were you sworn into?

Luce:

The RCAF.

Roland:

The RCAF. OK.

Luce:

Roland:

Yes.

Luce:

OK, Poole harbour, you go to the west and there's Swanage, Swanage Bay. Just a little bit north of that is this Worth Metravers. It's no longer there, it's a boys' camp now. But I worked there with them for the early part of 1941.

Roland:

Doing what kind of work?

Luce:

Evaluating radar. Well, they were teaching us the new equipment. and then we'd have to evaluate it under operational use. Most of the time I spent there was night-fighters with the search for hostile aircraft, with their gear. Then, towards the end of 1941, the raids on England had diminished to a point where there wasn't a great deal to do. But apparently the people in the know felt there was something coming up in the Far East. During our periodic medicals there was another Canadian and I went up to get our medicals. The doctor there was thumbing through, there was maybe 15 or 20 of us there. First order is, "Strip!" So we were divesting ourselves of our clothing, and the doctor called out, "You know, there's two Canadians here." He said, "Come on up." We went up. He said, "Problems with your throats, or anything like that?" We said, "No." He said, "Any problems?" He said, "Well, OK, you're all right.' So while we were getting dressed and going out and getting our papers from the clerk doing that, he said, "Do you fellows volunteer for overseas?" So we laughed and we said, "We are overseas." [laughter] So he said to him, well, he put down, "Yes." So three weeks later I'm posted [laughter]. That was how I - I don't know if I'd say got thrown out of England or not but how I left England, anyway.

Then, of course, things started declining very rapidly. After the battle of the Coral Sea, everything had gone. The Japs were starting to invade, and we tried to get out but we didn't make it. We were chasing all over the island. We had a boat, but we were turned in, so that was it.

Roland:

How do you mean, you were turned in?

Luce:

Well, natives squealed where we were.

Roland:

Ah, I see.

Luce:

The Japanese, once they invaded the place, would automatically put a price on any Allied personnel, put a price on their head. Of course, the leaders were poor. I don't think after being what you would say colonials for so long, I think that the Japanese had made them so many promises that they believed it. They felt, well, anything to get rid of the white man [laughter]. That was my personal thought, whether right or wrong. But they learned their lesson afterwards.

Roland:

So the Japanese came and collected you, did they?

Luce:

Yes. Then we were all assembled in Tasikmalaya, and from there they started splitting us up into working parties. I was with the party that went to a place called Moaspati, which was a very large maintenance airfield that the Dutch had built for their own air force.

Roland:

Excuse me can you spell that?

Luce:

M-o-a-s-p-a-t-i, I believe, Moaspati. So we spent quite some time there. We were doing different things. In other words, getting the airfield pretty well operational again. Basically it was that. Then we were split again and I was sent to Surabaya.

Well, in Surabaya we loaded ships at the dock. We tore down oil refineries, or oil storage tanks. While at Moaspati, too, we stripped all the maintenance gear, beautiful repair equipment, but that was all shipped out to Japan proper. Going back to Surabaya, we were loading ships, carrying all this steel, cleaning up rubble, sunken ships in the harbor, and bombed buildings and what have you. We spent, I'd say, six to eight months there.

Then they moved us to a place called Tjamahi, that's T-j-a-m-a-h-...I know it ends in an "i". There's a number of different spellings. Even Surabaya has about three or four different spellings.

Roland:

Yes, and Tasikmalaya I've seen as one word and two words.

Luce:

Right, yes, I've always known it as one word. But Surabaya is s-o-e, s-u-r, there's many different [spellings]. But this Tjamahi - we were in a camp there at which we were maintaining mainly Japanese equipment, trucks, mobile equipment, and we did a lot of that work up there -- forced, of course.

Then, from Tjamahi they picked out anyone that could walk and started sending them out to the islands. So the particular draft I was on was sent down to Batavia and we were just there a few days. It might be, I don't know if it has any bearing here, but at that time the Japanese had suffered some losses, and I think they were starting to take a second view of world opinion. That's in retrospect. I didn't think of it at that time, but I do now, as the reason they did it. But there was 2000 of us on this particular draft.

Now, we were in a place called the Bicycle Camp. You may have heard about it. The camp commander was a fellow named Sumi. That was his nickname. They hung him after the war. At the time, previous to this, right after capture, we all had to have our heads shaved. The Japanese now say that was for hygienic reasons; I think it was for humiliation, but be that as it may. Sumi -- when you went into camps you were searched. Now, if he found a comb, or anything pertaining to hair, growing hair on your head, he would literally jump up and down. He had to be unbalanced, that's all there was to it. He'd jump up and down, he'd beat the devil out of any prisoner found that way.

Roland:

This was a receiving radio, it wasn't a transmitter?

Luce:

Receiving. No, no, just a receiver, on medium band. Our wing commander knew I had it. Of course, the penalty for owning a radio, or operating a radio was death. That was it. But our Wing Commander Cave, he was an English fellow but he'd done most of his work in South Africa, and we used to get along pretty well together. You know, we sort of I guess our personalities didn't clash. He knew I had the radio so we had very little gear of course, going in and out of these camps, but we were searched, so we had a system of working, that he being the Senior Officer, would always be in the forefront. He would have his little bag of bits and pieces. He would be searched first and then he had to go out in front and order the rest of us to do whatever the Japs wanted. So, the system was, that I had all my stuff, including my radio, in my bag. So after his bag was dumped out and searched and all that, he'd be putting it in, and I would be next. See, I'd go up. But in the shuffle there'd be a little clumsiness there and he'd pick up my bag and walk off, and I had his bag searched again. We got through four camps that way! -- But finally things were getting much rougher. My name was engraved on the radio too, which wasn't exactly the best of things. So I buried that. I had a set of sidearms we had smuggled. They were buried too. So to the best of my knowledge, of course, they'd all be rusted out.

Roland:

You took a lot of chances didn't you, carrying a radio and sidearms?

Luce:

Roland:

Not very efficient.

Luce:

No. But I looked up once, and even under the circumstances I just about burst out laughing, because if you can see all these bare bottoms, and the Japs, most of these bottoms of the fellows who bent over come up almost underneath their armpits! [laughter] It was a sight to behold. It is a sight I can still retain very clean in my memory.

Roland:

It's too bad you're not an artist.

Luce:

Yes, it is. There was a Leo Rawlings, and oh, the other fellow he was cartoonist for Punch magazine.

Roland:

Searle?

Luce:

Ronald Searle. He was in our camp, both of them. Well, we were in camp together. But Ronald Searle was in Tasikmalaya and he was in Moaspati. He went to Surabaya with us. Then they went one way and we went the other. But he was there too. In fact, he did a couple of cartoons of me.

Well, to go back to Sumi and his camp, after we had these tests, they took us out by a barge to a ship called the France Maru; it would be a freighter, I would guesstimate about 12 or 15 hundred tons. The harbor in Tandjong Priok, which is the harbor for Batavia, was littered with sunken hulks. The ship was anchored where it was accessible to the sea, and the 2000 of us were marched up on foot, some in the front hold and some in the stern. But what they did there, they gave us 18 inches or half a square meter of space. You stood in there, and then they closed the hatch down and they had the canvas vent pipes. Now, if you wanted to sit down or stretch out or anything, everybody else had to cram over. You were allowed up on deck once a day, once in 24 hours for about an hour, eh? They lowered down a bucket of rice to you. We had five days on that ship. And we went to Palembang.

Now, Palembang is about one or two degrees south of the equator. When we arrived there at noon (I had a watch, I was still smuggling at times, so I knew what the time was). But when I stepped off that, we were all dehydrated completely and they had one water pipe on the dock. That had the biggest crowd you could imagine around it. But when I stepped off that ship out of the hold, I started shivering. You know, I can become so used to this temperature in the hold that you come out into what would normally be a hot day, I was cool, I was cold. So the human body must be very, very adaptable.

Roland:

It sure is.

Luce:

So from there we went by truck into

Roland:

Excuse me: before we get away from the ship I want to ask, what about latrines?

Luce:

Latrines: you had a bucket on that ship. It was just a bucket. When it got full, up it went. But of course, there would be 1000 in our hold and 1000 in the rear hold a lot of those fellows had dysentery. The smell! They show pictures and all that, but nobody has every come up with the smell. That's a memory that's very strong in my mind. I can't describe it, but it was there.

So we got to Palembang and we went to this place called Pangelam Bali. That was two names. P-a-n-g-e-l-a-m, I believe, and Bali, B-a-l-i, I think. Don't trust the spelling too much. It's something like that. We spent 18 months there. There were three hills. The Dutch, in the 1940s, I guess, '41, had started to build an airstrip to protect the oil refineries at Palembang, because at that time they were the largest oil refineries in the world, I believe. Which could have been partially demolished by the Allies before the Japs overran them. But the Dutch had gotten mechanized equipment, and they had maybe, oh, 300 to 400 feet of runway started to be cut.

Roland:

You had done something for the war effort.

Luce:

Well, for our own, at least. It made us feel a little better. We had a few other things there of that type. It was grim in those places. Food was mainly rice.

Roland:

Yes, tell me about the food.

Luce:

Yes. The sweet potato leaves was our vegetable. Rice was our main staple. Little if any meat or fish. The meat, we used to love to see the bombers come over and bomb the refinery, because it seemed to me there was a dandy Intelligence effort going among those islands somewhere. We knew nothing of it, but just the facts. They had a group of fellows working on the oil refinery, getting it going. As soon as a section of that oil refinery would start to run, within a week, there'd be an air raid on it. Of course, [some of] the bombs would miss and hit the river and kill fish we'd get the fish. So that was that. But apart from that, when there was no raids, the Japs got dry salt fish. That was their protein. We never got any; we were suffering from it. But to add insult to injury, the ration trucks would come up from Palembang and they'd put our people on unloading it. So, again, all these sacks of dried fish get the guards talking with their back to it, and then every body would line up and urinate on their fish. I know it didn't do a doggone bit of good, but it made us feel a little better. So ..- that was basically it.

Then we had our dry season there, in which water was down to a pint mug a day per man. There was a high sulphur content in it, and when you drank that water your mouth would feel furry, and you'd need another drink. But that was one of the worst things. And no salt. In fact we must have gone six months or more with no salt at all, and then we got two, three ounces of salt; I ate salt until I was almost sick. It was a craving that you had. But the rice we had, boiled rice in the morning, a pint mug.

Roland:

Was there any trading with the natives? Could you get things that way?

Luce:

That was punishable. The Japs themselves as I say, I had a watch and a ring, which I'd smuggled. In Sumatra, OK, I sold my watch and ring, so I could buy from the natives buy some beans or whatever you could get to help your diet. That's the only way you could really stay alive. After we finished that job in Sumatra, they put us on another boat. But this time, I guess, the war was really getting tight because this would be early in 1945, somewhere around it would have to be after Christmas and New Year's. I would say somewhere around about February, March.

Roland:

So you spent all of '44 at this job and part of '43.

Luce:

Yes. Then they took us down to Palembang and we would have been there a couple of days, and then they put us on a little oil tanker. By this time, our 2,000 were no longer 2,000; we were down to between 600 and 700. Dysentery, malaria, beriberi. Pretty well all of those. We all had it. I mean there was no question about that. They put us on as deck cargo. Apparently the allied submarines were really reducing their marine transportation. But that, to my mind, was the best trip we ever had courtesy of Tojo. Because we were on deck, OK, it rains you got wet, but you weren't in that hold with the smell and the stink and everything like that.

Our latrines here, this was a very little ship, as I say, oh, it would be under a thousand tons I would say, and very low in the water, and our latrines in those days, when we were in the bow, or in the bow section, was a plank that went out over the side of the ship. So when you had to use the latrine you climbed over the rail and you squatted and hung onto the rail. Every once in a while you'd get whipped by a bow wave or something like that [laughter]. There used to be a standing story or joke around there: "What happens if a shark comes up?" [laughter]. "You'll be talking in a high voice."

But we went to Singapore then, because we were all, I would say, pretty well down the ladder as far as health went.

Roland:

Yes, let me just take a break there before we get onto Singapore, and let me ask more about conditions in Java and Sumatra. You said that your group went from 2,000 to maybe 600 or 700. Did you have medical people with you?

Luce:

We had one doctor that came from Scotland. Incidentally, our little bugs that we had in the rice, we were so low on protein that for the worst cases of avitaminosis or lack of protein, he used to take these little bugs, or the worms, he'd feed them on rice water; after, I don't know, a week or two when he felt they were cleaned out of any bacteria or germs they might be carrying, he used to fry them in palm oil. The worst cases would get two tablespoonfuls of fried maggots that's what it was for protein. That was his only way that he could at that time.

Roland:

What was his name? Do you remember?

Luce:

No, I don't, I'm sorry. He was a Scotch fellow, an awful nice guy, but his name I can't The only one name that stands out in my memory is Dr. Tierney; he was 242 Squadron doctor. He was an Irishman, and he was the only man that I saw, amongst many, that could stand up and talk the Japs down without getting the devil beat out of him. Dr. Tierney, he was a, well, during the heavy days before we ever got captured, he was always right in there with the fellows, and looking after them. Even if you weren't complaining about anything, he'd put the finger on you; he'd say, "Go do this." [laughter] Dr. Tierney had just a ring of hair, you know, somewhat bald on top. We used to watch him when he'd get in an argument with a Jap officer, you could see the red coming up. (Of course, he had no shirt either.) When that red met at the top, that was something similar to an atomic explosion. Oh boy, I often wondered if he's...I've been trying to trace him but I haven't found him yet. I have heard word he's still alive and practicing in Ireland. But I'm not sure of that. He'd be a great character to meet.

Roland:

Yes, yes indeed. How was your personal health in Java and Sumatra.

Luce:

Roland:

The wet beriberi? The swelling and

Luce:

The wet beriberi. Swelling, yes, like say at your leg, all of a sudden there'd be a ridge. You'd wonder that the skin wouldn't break, it seemed to be so tight with the pressure in there. And my eyes went down. Like where you are, I could see you but I wouldn't be able to recognize your features. Again, I think everybody had that. I don't know who it was, now, that came up with the thought to get rid of that fluid, drink coffee. Well, coffee was plentiful and we started drinking this strong coffee. Gosh, you'd head for those latrines, and you'd think you're never going to stop. You'd turn around and come back that got almost as bad as dysentery. But it seemed to get rid of a lot of the fluid. I don't know the reason for that but

Roland:

How about your weight?

Luce:

Roland:

OK. One more question or two, then we'll go on to Singapore and talk about that. Do you recall, were you getting any sort of medication, or were you getting pills or shots, were there any immunizations against diseases?

Luce:

During our captivity?

Roland:

Yes.

Luce:

No, no.

Roland:

Nothing at all?

Luce:

Roland:

Were you with "Paddy" Leonard [HCM 17-85]?

Luce:

No, but Paddy and I were in a place called Tjilatjap in Java. This is where we were trying to fix up a boat to get away. Now, Paddy was there. I can remember those fellows digging in on the beach. This was before we got captured. Then we went further on down into the jungle to get this little Dutch patrol craft, trying to get it going. Then Paddy, I guess they went the other way, so we were at one time in the same town together, the same port, but I didn't know him. He went into Sumatra, but he went in the southern area, southern, we were more mid-Sumatra, where we were working. But I know him, of course, now, from the POWs.

Roland:

Yes. I have interviewed him also; I'd forgotten to mention his name earlier.

Luce:

Oh, yes, yes. I understand he's been sick. I was up to a meeting early this month and apparently he'd been sick.

Roland:

Oh, I didn't know. I saw him within the last week.

Luce:

Oh, well he must be out of the hospital then.

Roland:

Oh yes, I was at his home. I picked up some papers that he was giving me and

Luce:

Oh, oh, very good. I have some but they're out right now -- evaluation tests made by the British Institute of Tropical Medicine. They were taking groups of a thousand former POWs from the area that both Paddy and I were in, and running down how many cases of this and that, and half of the things I don't recognize the technical name of. One thing that struck me as funny, in fact I kid the doctor I go to about it, is out of every 1000 there's 475 that had to have some form of psychiatric treatment, be it small or large. I tell him, you better get me ready for the Norris Wing. [laughter] But it seemed to me an awful lot of people.

Roland:

It is a lot of people. I guess a lot of people had a lot of strains and pressures and

Luce:

We had one fellow...things weren't just the way the history books would like you to believe, in Singapore, it was a fiasco. It seemed to me that the people in charge of Singapore had been sort of gently removed from England and put some place where they couldn't interfere, when England had a war on, so they sent them out in the '40s, '41. Of course, they made the same mess-up out there. This one fellow that I can recall, I can't think of his name now, he was so angry that he wouldn't speak to anybody not even his own people. I remember him getting liberated. He just went from one prison to another.

Roland:

You mean the civilian prison after the war?

Luce:

Yes. Well, he went into a mental institution. I mean, it's a prison. In fact, he's a fellow that lives down at Niagara-on-the-Lake, he was also in the Royal Artillery that Paddy was in. This fellow, he was one of my foremen, out at Niagara Parks. I spent my last four, five years out in Niagara Parks, you see, as superintendent of maintenance. Tom Ellis is his name - he was captured. But he tells me he spent two years in a psychiatric ward after the war. He's all right now, but at that time he was very depressed.

Roland:

OK. I interrupted you; please pick up the story again there.

Luce:

Well, as I say, we went to Singapore on this little oil tanker, and they sent us to Changi, the famous Changi. Now, while we were not inside the stone walls, we were in little grass huts outside the gate. It was a big compound there, I think there must have been 20,000, 25,000 people from that area. It was the biggest, I think. So we spent three months there and we didn't do anything apart from the usual what they used to call "bullshit" down there. [laughter]

We got fed up and then we were sent out to a working camp at Kranji. You may have heard of that one. That's up near the naval base. In that camp we were digging tunnels into the sides of the hills. You drive two tunnels in, and then a "U" to meet them. Now, apparently they had tried this in the islands in the Pacific. The Japanese had tried these. As the Allied forces invaded, they'd go in there, and come out behind them. But I don't think they worked out too well because I understand, reading history later on, that they'd either bulldozed the entrances closed or put explosive charges in there, and seal them up that way, and let the Japs stay in there. So we were digging those. We had to do these tunnels. That's where I was when the war ended, digging tunnels.

always maintain -- we used to talk about this a lot in prison camp, how the war was going to end I think of the group I used to chum with, we all had a feeling that we were going to make it. You know, every one of us were definitely going to try. There were times though when this is digressing a little bit -- but there were times throughout the camps, especially in Sumatra, when you were pretty sick, but you had to work. You were feeling kind of blue, and the thought of, "What's the use of going on?" would cross your mind. I know in my case (I never discussed this with any of the fellows there maybe in a lighter vein, but never seriously), that, if I'm going, I want to take three with me. I could never see a way of taking three. You'd get one, maybe if you were lucky two, but I could never see getting that third one before they got you.

Roland:

That's a lot.

Luce:

Well, that was my detraction. My price was three, so I never done it. But it was those things that you had to do. But you'd keep it in a light vein. Now, some of them would be very despondent, very, very despondent. Others weren't. Well, I guess everybody was despondent, but not that much so.

Roland:

Were you a smoker?

Luce:

Yes,

Roland:

Were you then?

Luce:

Oh yes, heavy. But we didn't have cigarettes, see. That was a silly thing I did when I got out everybody was giving me a cigarette, so I smoked. I should have stayed off it because I stopped 25 years ago, I guess, I'd stopped for good. I could have done it then because we weren't getting them. In fact, you know, after we got liberated, the navy came, they liberated us and gave us cigarettes, and after two weeks we were giving them cigarettes. We had all their cigarettes [laughter].

Roland:

One of the things that I like to ask about is, what about sex, what about the absence of sex? Was this a problem?

Luce:

Roland:

Any signs of homosexuality at all, that you know of?

Luce:

Never that I saw. I look back now, with today's media reports on that, and thought, what was wrong with us? -or what was right with us? whichever way you want to say it.

Roland:

It seems very different, doesn't it, now?

Luce:

It does. I can't understand it. Because in those days, when I was young, everyone had the urge, but I think our morality was such that there were very few girls that I ever knew of were willing to go along with you. But today, it seems to me the young girls of today, they seem to think nothing of it.

Roland:

The rules have changed a lot.

Luce:

They have. Now why

[End of side 1.]

Roland:

Tell me a bit about brutality. You talked about the routine getting smacked around and so on, what was the routine?

Luce:

Well, say you were sick; in the morning we had to line up for what they called tenko, they'd count you off. Then they'd split you up into working parties. If it wasn't a big job like the airfield, OK, they'd have 30 guys go here, 100 go here, depending on what the job was. If you were too sick to go out to work, they'd come into our little grass huts, and they'd say, saki," "sick." OK, you'd get a kick in the back or a rifle butt. Now, if you didn't move, if you were sick, nothing is going to bother you, especially malaria or something like that. Stop the world and get off. That's all there is to it. If you didn't move, OK, they'd leave you and go, but if you would wince or try and get out of the way, zip, out to work, that was it.

Roland:

OK. To go back to the example you gave before, of the sick people being kicked and made to go to work and so on, now, did the doctor, the POW doctor, did he have any control over the guards?

Luce:

Not over the guards, no. He could just say, "the man is sick," and if he insisted too hard he'd get beaten up. He could recommend, and say, "No, he's too sick," or something like that. Again, I'm talking about the small jungle camps. In the big cities there was generally a Japanese doctor around and they'd get into a real big hassle about it or something like that, but in the small jungle camps you were at the mercy of the commandant. At least, that's been my experience.

Roland:

What was the worst camp you were in, in your opinion?

Luce:

Of course, the standard stuff with a cigarette butt quite normal standard practice no matter where you were, that type of thing. But I think the worst thing of all was, somebody might have tried, or got caught making an attempt to escape -and this was more in Java than in Sumatra, because in Sumatra we knew there was no place to go but in Java there were places where they'd actually beat them to death. They'd bind you up, and of course there was machine-guns on you, out of the whole group there, and they'd beat them to death or bayonet them to death. Seldom did they ever shoot them. Nothing that fast. It always seemed to be a slow torture. It seemed to suit their mentality, or requirements.

Roland:

What about your working schedule when you were at this camp in Sumatra? Did you work every day? Did you have days off and rest days?

Luce:

Oh yes. One in ten, one in ten, that was our average. But there, we were on a quota system. Again, nearly every place was quota. except for things like loading ship or something like that; when you were up to the stakes, OK, and if you didn't get up to the stakes by dusk, you stayed there until you did, unless the weather got so bad that you couldn't do it. I think one of the worst jobs At the airfield job, we could sort of break ourselves in on it, but I think the worst job was loading ships. Now, you had to go on to the dock and up the little companionway, the ship's ladder. Sugar, rice, that was all right, they were in 100-kilo bags. What happened, you'd bend over and there'd be two prisoners, they'd sling a bag up across your shoulders; well, that would fit the contours of your back. You'd go up, and you'd go up to the deck, at the hold, then you'd drop it at the hold and they'd lower it down. Another group would be lowering it down. Well, that you could get used to. That was heavy work, I mean 220 pounds on your back and you're not exactly the best of shape.

But the worst thing of all was loading tin ingots. There was two ingots, and they were 50 kilos apiece, in a wooden box, about so big. And that box doesn't give. They get that on your shoulder and away you'd go. But by the end of the day, or even before the end of the day, your skin would all be raw and bleeding with the chafing of the corner of this wooden box. That was a deadly one. Or oil drums - that was another bad one. They'd have two of you with what was a 45-gallon oil drum. You'd have the rim and you'd have to sling them, and pile them up. That was a good one for getting your fingers and so forth, if you weren't coordinated with each other.

Roland:

Were there any bad apples in the camps?

Luce:

Yes, yes.

Roland:

Can you tell me a bit about that? I don't care about names.

Luce:

I can't think, I've been trying to recall his name when my friend was out here from England. We went through it again and neither one of us could. But there was an Australian Wing Commander the Japs had set the camp rules, and he religiously said, "Everyone will obey these Japanese rules." Well, nobody saw eye to eye with him let's put it that way. If we could break the rules, we'd do it. He, on occasion, had turned some of his own men in, and had reported them to the Japanese. personally heard the Australian fellows tell me, they said, "One day the war's going to be over, we're all going to get on a ship and go home," they said, "and you're going to get on that ship but you'll never get off it." I've been trying to see [find out], because those fellows would do it. They were the type that would do it.

But we had collaborators. I think the Dutch were worse than anybody else, really. Even after we first got captured there was a Dutchman in Java, he told me, he said, "I feel sorry for you." I said, "Why?" He said, "Well, you're going to remain in prison till the war ends," he says, "but the Japanese can't run this island without us." But they did and he stayed there too. The Dutch women had much more spirit, fight, against the Japs than the Dutch men did, I think. I think that a lot of people that worked in the tropics got so used to a lazy life, having everything waited on hand and foot, all they had to do was apply their mentality, really, and someone else would do the physical work. I think there's a tendency to get lazy.

Roland:

Were there any good times?

Luce:

Oh yes. Well, to lift our morale, yes. Like in Singapore. Of course that was the "Statler Hilton Changi." It was the Statler Hilton of any prison camp I've been in. That was great. With all those people there I think there was every talent conceivable available in that camp. They used to put on plays and that; I remember the last one I saw there, before I went up to Kranji, was a show called Under the Sun. Well, that in itself speaks exactly what it was. Of course, the first night of any performance the Jap commandant and all his retinue were right in the front row. This play, it was something out of this world. Now, had they only listened carefully or been able to understand, those Japanese who could speak English, there was no doubt about it, but they didn't understand it, because that really took a ride out of them. They were all laughing and clapping, and they were getting the worst insults that it was possible to give. I was a play but you were really giving it to them. You know, I enjoyed that myself.

Oh, and different things we used to do. We used to steal off the Japs every occasion we could. On this last working party digging tunnels, there was another fellow and I, this English fellow, we were about the two biggest in the party. So we were delegated to go on a truck with a Japanese guard and driver down into the city of Singapore and pick up lumber to make the props and linings for the tunnels. Well the lumberyard we went to was right next to the Singapore Cold Storage. The people running the Cold Storage would slip us meat. Well we'd smuggle that back on the truck. Our working party was around 30, 35 people, and we used to have our little tea barrel with a wooden lid on it. So the people in the engineering division we were working for, they'd bring us to the camp, divide us up, and then our guards would take over and they had to count us and search us. So what we used to do, the meat was in the bottom of our little barrel, the wooden tub, and we'd put the lid on it but cock it up so that it was about a 45-degree angle, and you'd put that on the steps of the guardhouse. So as the guards came down they had to circle around it to search you but they'd never look in the rice barrel or the tea barrel things like that.

Then we'd be out in the rubber plantations, and you'd get snails off the trees. So you slip them into your G-string [laughter], and bring them in that way. Another thing we used, well after our release they were, all the sealings around every mine, and so forth, and they were sweeping them, and they were waiting for ships and then sort of sorting us out who had to go on a hospital ship and who could go walking wounded. After the Allied forces came in, I guess it must have been two or three weeks, and there was no sign of being moved out. So we were taken over by an organization called the Repatriation of Allied Prisoners of War and Internees. I don't know if you ever heard of them. So after about two or three weeks and some

Roland:

RAPWI.

Luce:

RAPWI, yes. Well some wag there I don't know if you ever heard changed that around: in place of "Repatriation of Allied Prisoners of War and Internees" to "Retain all Prisoners of War Indefinitely" [laughter]. Well, that seemed to start a move because we got out of there pretty quickly after that. -...."ž Oh, there was many things that went on that were humorous. You can't think of all of them at one time,

Roland:

-

Is there anything else that comes to mind that's medically related at all?

Luce:

When I first came home I used to get malaria once a month. I had this tertian malaria every 30 days; boom - I'd be shivering and shaking. There used to be a Dr. Cunningham in St. Catharines. He's dead now but he was the DVA doctor, and he'd come down to the house, of course I wasn't married then, I was back home with my family. My mother used to get awfully worried. He'd say, "You've got to go in the hospital." I said, "What for? We used to work with it." He said, "What did you take?" I said, "Nothing." Oh, he always used to get so worried about this malaria. Well, I never did go in the hospital. Another thing I found out

Roland:

How long did that go on?

Luce:

Well, it started weaning off after eight months, nine months. In place of every month it started spacing out. It got to the point where unless I got run down for some reason, I didn't get it. Then I wouldn't get it nearly as bad - just maybe for a day, 24 hours with a high fever or something like that. I used to take quinine. There was an old fellow that come from World War I; so when he got it he'd take this quinine until his ears started plugging, he said, "and then I'd get a big tumbler full of whiskey." And, he said, "I'd start drinking it quite fast." He said, "When I woke up I was all right." You know, you would but you'd be drowning in the bath [of perspiration], everything would be soaked.

Then later on, after about two years, I'd be having a slice of bread and butter, and just [biting into] the soft part of the bread, here a piece of tooth would come off. I reported that to the DVA and, "You just got poor teeth." So OK, I didn't bother no more. In the early '70s, around 1970, '71, something like that, I received a letter from the DVA stating that over the last few years they had found that the tooth problem was common, from a lack of vitamins and so forth. So they asked me if I would care to undergo a medical and dental exam. I said, "sure." I'm on their list now for free dental. One of these dentists down at St. Catharines that looks after me he does a great job. He really looks after them.

Roland:

Well, there's some benefits.

Luce:

Oh yes, yes, yes. I find now, too, that again I had never related them, but over the past five or six years, in the late 70s at different times I'd have to get medicals. Doctors I'd never seen at any time before, during a check-up they'd say, "You've got an arthritic back." "Well it doesn't seem to do anything," but lately I find it is bothering me. Both the back and my knees now, arms and shoulders; I think that was caused by, well sleeping in the rain. I know that in Sumatra (again, that's ..., a deadly place) we'd have to sleep on the ground in the little huts. There'd be rain puddles, and you could actually warm a rain puddle up to where you can sleep. The water -your- temperature will drop or it will come up, I'm not sure which, but that's what it would do. The only thing that will wake you up is a drop of rain falling through the roof and splashing in your face. But you can actually adjust to sleeping in a puddle of water. It seems funny.

Roland:

No, I don't.

Luce:

Cecil Shaver. He's got to be 80 years of age now. But he's been in this all his life. I finally wound up seeing him and he found out I'd lost about 30% of my blood, and he said, "OK, that's your problem," but he said, "I don't know why." That started off another round. Then they found that I was bleeding internally, and after they checked oh, I had an ulcer, a hiatus hernia with an ulcer on it. But it wasn't bleeding that bad. But apparently in my intestines I had this, what they called diverticulitis. Well, once they found out what it was, they treated me treating it for it iron, sulphate, etc., my blood came back up and I lost this dizziness, or whatever you call it, dizziness. I asked DVA, would there be any connection with the diverticulitis and dysentery? Because I understand it's like little blood blisters.

Roland:

Little pockets on the bowel, yes.

Luce:

Well, what I was questioning was, would the dysentery weaken my bowel so that they might form more readily than otherwise? So I went up to Hamilton, they asked me to go for a medical. There was a lady doctor up there, an Irish lady, and she said, "I've got an appointment with you for a specialist to see." But he said, "Oh, dysentery is nothing more nor less than diarrhea," but I don't think he's ever seen real cases of dysentery. Anyway, that's all that came out of that.

Roland:

That reminds me you mentioned earlier that you had both bacillary dysentery and amebic dysentery. Can you tell the difference? I mean, does somebody who has them tell the difference between these two. I don't know. I've never had either one.

Luce:

Well, microscopic

Roland:

I know microscopic, yes, but as a patient can you say, "Oh, now I've got amebic dysentery"?

Luce:

Well, generally, I'd say offhand, thinking back now, because when I had dysentery everybody had to work in the camp. If you had dysentery, you still had to work. Well, they put me in the hospital. I was doing microscopic work examining slides, in other words, seeing what was what. Judging from what I saw on the slides, and the patients' reaction, it seemed to me that bacillary dysentery was very violent but short-lived. Whereas amebic dysentery was somewhat less violent but very, very prolonged. That would be my impression. I wouldn't state that as a fact but it seemed to me to be what I seemed to observe.

Roland:

Where was this that you did this lab work?

Luce:

In Java, in Bandong. We were up in the mountains there to get rested up.

Roland:

What kind of lab equipment did they have? They had a microscope, obviously.

Luce:

They had a microscope there, and about all the technical equipment. I mean, the surgeons had some instruments but I'm not too familiar. There was no x-ray or anything like that, of course. There was just the microscope and the dyes and so forth. In fact, they had one in Kranji. Because I know one time the doctor there, he said, "They're going to check on youfor malaria. That's what he came out and he said he does thecheck there.

Roland:

Well then, very good.